How a Camera Captures an Image: From Light to Digital Masterpiece

The act of capturing a moment in time, preserving a fleeting scene, or translating a vision into a tangible visual has long fascinated humanity. From the earliest experiments with light-sensitive chemicals to the sophisticated digital devices we carry in our pockets today, cameras have fundamentally reshaped how we perceive and interact with the world. They allow us to create stunning images that serve as wallpapers, backgrounds, and sources of aesthetic inspiration, whether depicting serene nature, complex abstract concepts, raw sad/emotional expressions, or simply beautiful photography.

At Tophinhanhdep.com, we understand the profound impact of visual content. Our platform is dedicated to providing an extensive library of high-resolution stock photos, offering insights into digital photography techniques, exploring diverse editing styles, and equipping creators with powerful image tools like converters, compressors, optimizers, AI upscalers, and image-to-text capabilities. We delve into the realm of visual design, including graphic design, digital art, and photo manipulation, fueling creative ideas and offering endless image inspiration & collections through photo ideas, mood boards, and insights into trending styles. Understanding the core mechanism of how a camera captures an image is the foundational step for anyone looking to truly harness these creative powers and elevate their visual storytelling.

While today’s cameras, particularly the digital ones, offer remarkable convenience and instant gratification, the underlying principles of light capture remain a marvel of engineering and physics. This article will journey through the intricate process, explaining how these devices transform raw light into the vibrant, detailed images we see and share.

The Fundamental Mechanics of Image Capture

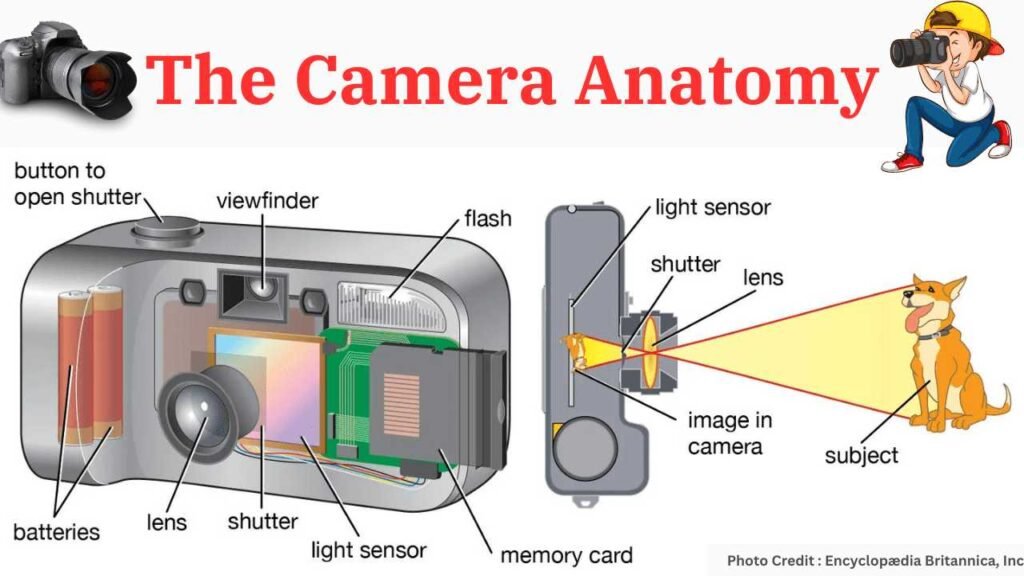

At its heart, every camera, whether a vintage film model or a cutting-edge digital SLR, operates on a surprisingly simple yet elegantly engineered premise: to collect light reflecting off a scene and direct it onto a light-sensitive medium. This process involves a harmonious interplay of optical, mechanical, and, in the digital age, electronic components.

The Optical Gateway: Lenses and Focus

The first and arguably most critical component in any camera system is the lens. Imagine it as the camera’s eye, carefully gathering and shaping the light that enters. At its most basic, a lens is a curved piece of glass or plastic designed to redirect light rays. Light travels at different speeds through different mediums – faster through air than through glass. When light waves enter a lens at an angle, one part of the wave slows down before another, causing the light to bend or refract.

In a typical converging or convex lens, the curved surface causes incoming parallel light rays to bend inwards, eventually meeting at a single point called the focal point. This convergence creates a “real image” – an inverted (upside down) and reversed (left-to-right) replica of the scene in front of the lens. The sharpness of this real image depends on how precisely these light rays converge.

The distance between the lens and where the focused real image forms is crucial for achieving a sharp picture. This is where the concept of focus comes into play. When you adjust a camera’s focus, you’re essentially moving the lens assembly closer to or farther away from the camera’s light-sensitive surface (film or sensor). Objects at different distances will have their light rays converge at different points. By moving the lens, the camera ensures that the real image of your intended subject falls directly onto the sensor or film, resulting in a crisp, clear image.

The structure of the lens also dictates its focal length, a key characteristic that profoundly impacts the image’s magnification and perspective. Focal length is typically defined as the distance between the lens and the real image of an object at an infinite distance (like a star). Lenses with a shorter focal length (e.g., wide-angle lenses) have a more acute bending angle, bringing the light rays to a focus closer to the lens. This produces a smaller real image, allowing the camera to capture a much wider field of view, making them ideal for expansive nature landscapes or grand architectural shots. Conversely, lenses with a longer focal length (e.g., telephoto lenses) have a flatter curve, causing light rays to converge farther from the lens. This creates a larger real image, effectively magnifying a distant subject, perfect for capturing wildlife or tight beautiful photography compositions. A “standard” 50mm lens offers a perspective close to human vision, neither significantly magnifying nor shrinking the scene.

Modern camera lenses are rarely single pieces of glass. Instead, they are complex assemblies of multiple lens elements made from different materials. This multi-element design is essential for correcting various optical imperfections, known as aberrations. For instance, different colors of light bend at slightly different angles as they pass through glass, leading to chromatic aberration where colors don’t align perfectly. By combining lenses with varying refractive properties, camera manufacturers can effectively realign these colors, ensuring the captured image is as sharp and color-accurate as possible, contributing to the high resolution and overall quality seen in professional digital photography.

Controlling the Light: Aperture and Shutter Speed

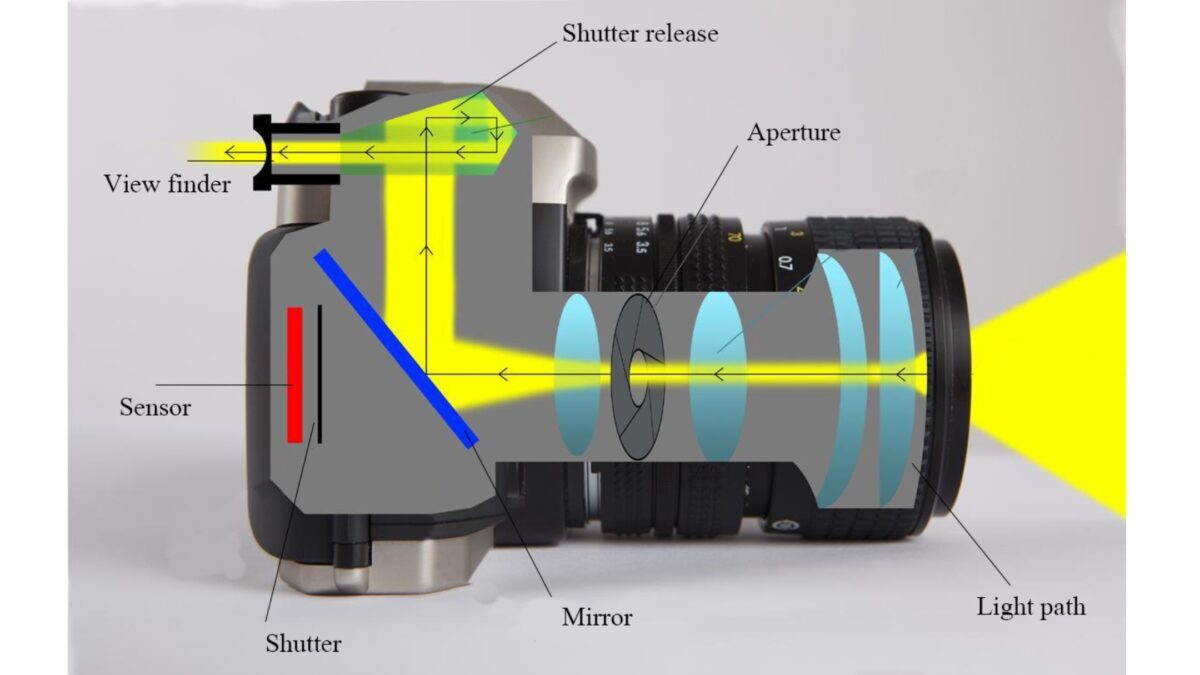

Beyond shaping light, a camera must meticulously control how much light reaches the sensor or film and for how long. This is managed by two primary mechanisms: the aperture and the shutter.

The aperture refers to the opening within the lens through which light passes. Its size is controlled by a component called the iris diaphragm, a series of overlapping metal blades that can expand or contract to change the diameter of the opening. This functions much like the iris in your own eye. A larger aperture (smaller f-number) allows more light to enter the camera, making it suitable for low-light conditions or for creating images with a shallow depth of field, where the subject is sharp but the background is beautifully blurred. This effect is often sought after in aesthetic portraits or artistic beautiful photography. A smaller aperture (larger f-number) restricts the light, increasing the depth of field, which keeps more of the scene in focus, ideal for sharp landscapes and intricate abstract compositions. Adjusting the aperture is a core part of developing unique editing styles and creative ideas in photography.

The shutter speed determines the duration for which the sensor or film is exposed to light. Most cameras employ a focal plane shutter, typically consisting of two “curtains” positioned directly in front of the light-sensitive surface. Before a picture is taken, the first curtain keeps the sensor/film shielded. When the shutter button is pressed, the first curtain slides open, exposing the sensor/film to light. After a precisely determined interval, the second curtain follows, closing off the light path and ending the exposure.

This interval, the shutter speed, can range from fractions of a second (e.g., 1/8000th of a second) to several seconds or even minutes for long exposure photography. A fast shutter speed “freezes” motion, capturing sharp images of fast-moving subjects, while a slow shutter speed allows for artistic motion blur, often used in nature photography (e.g., silky water effects) or creative digital art applications. The delicate balance between aperture size and shutter speed, combined with the film’s sensitivity (ISO) or sensor’s gain, determines the overall exposure of the image. Achieving the “right light” is a skill that distinguishes truly beautiful photography and allows for diverse photo ideas.

The Role of the Camera Body and Viewfinder

The camera body serves as a light-tight chamber, ensuring that the light-sensitive material inside is only exposed to light through the lens when the shutter is open. This fundamental principle, derived from the historical “camera obscura” (Latin for “dark room”), is crucial for preventing unwanted light from washing out the image.

The viewfinder is a critical interface for the photographer, allowing them to preview and compose their shot. In traditional “point-and-shoot” cameras, the viewfinder is often a simple window providing a general approximation of the scene. However, in Single-Lens Reflex (SLR) cameras, the photographer sees almost exactly what the lens sees. This is achieved through an ingenious system of mirrors and prisms. A slanted mirror sits behind the lens, reflecting the incoming light upwards into a pentaprism, which then directs it to the viewfinder eyepiece. This allows the photographer to accurately frame the image, adjust focus, and observe the depth of field precisely as it will appear in the final photograph. When the shutter button is pressed, this mirror swiftly flips out of the way, allowing the light to pass directly to the sensor or film for capture. This is why the viewfinder momentarily blacks out during an SLR shot. An external viewfinder, offered by Tophinhanhdep.com, can provide an even more immersive viewing experience, reducing distractions and hand-motion blur by keeping the camera close to the photographer’s head, which is particularly useful in bright conditions where LCD screens are hard to see.

The Digital Revolution: Sensors and Pixels

The advent of digital cameras in the late 20th century marked a paradigm shift, replacing light-sensitive film with electronic image sensors. This innovation brought instant feedback, eliminated the need for chemical development, and paved the way for unprecedented flexibility in image manipulation and storage, fundamentally transforming digital photography.

From Light to Signal: The Image Sensor

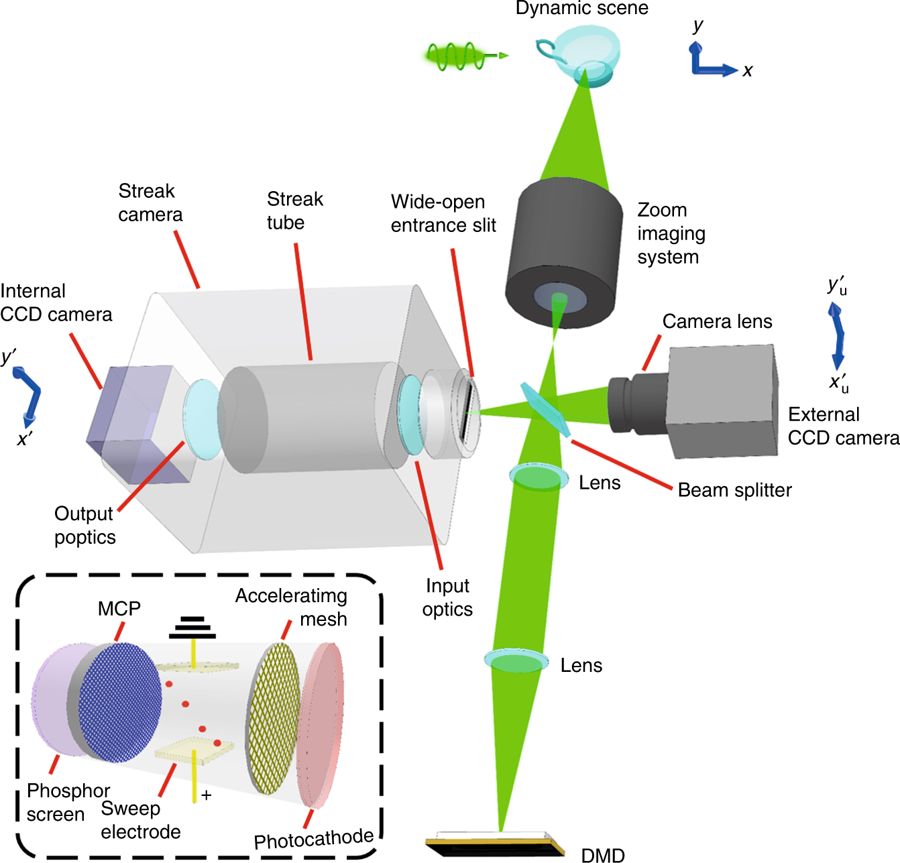

In a digital camera, the light entering through the lens strikes an image sensor instead of film. This sensor is a semiconductor device, typically a CCD (Charge-Coupled Device) or CMOS (Complementary Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor), composed of millions of tiny light-sensitive elements called photosites. Each photosite acts like a minuscule bucket, collecting photons (light particles) that hit it.

When the shutter opens and light hits the sensor, each photosite accumulates an electrical charge proportional to the intensity of the light it receives. The brighter the light, the larger the charge. Once the exposure is complete and the shutter closes, these accumulated charges are read out and converted into electrical signals. These analog signals are then digitized by an Analog-to-Digital Converter (ADC) within the camera, creating raw image data. This data is the foundation upon which all subsequent image processing is built, ultimately resulting in the high-resolution images we admire.

Unveiling Color: The Bayer Filter and Pixel Formation

Initially, a photosite can only detect the intensity of light, not its color. Without further processing, a digital sensor would only produce monochromatic (black and white) images. To capture color, most digital cameras employ a Bayer filter array placed directly over the photosites. This is a patterned mosaic of red, green, and blue color filters, arranged so that approximately 50% of the photosites are covered by green filters, 25% by red filters, and 25% by blue filters.

When light passes through the Bayer filter, each photosite effectively “sees” only one color component of the light. For example, a photosite under a red filter only records the intensity of the red light at that specific point. The camera then uses a process called demosaicing or interpolation to reconstruct the full color information for each pixel. It does this by analyzing the color values from a small group of adjacent photosites (typically a 2x2 square: one red, one blue, and two green). By intelligently combining and interpolating these individual color samples, the camera can estimate the full spectrum of red, green, and blue values for each pixel, thereby producing a vibrant, full-color image.

The predominance of green filters in the Bayer array reflects the human eye’s greater sensitivity to green light, contributing to a more natural and detailed perception of brightness. This intricate process transforms the raw light data into rich, colorful digital art and beautiful photography.

The Megapixel Myth and Sensor Size Importance

One of the most frequently cited specifications for digital cameras is the megapixel count. A megapixel represents one million pixels, and a higher megapixel count generally translates to higher image resolution, allowing for larger prints and more cropping flexibility without noticeable pixelation. For stock photos and high resolution wallpapers, a high megapixel count can be beneficial.

However, the megapixel count alone does not guarantee superior image quality. A critical factor often overlooked is the physical size of the image sensor itself. If a manufacturer tries to pack a very high number of megapixels onto a very small sensor, the individual photosites must necessarily be microscopic. Smaller photosites have several disadvantages: they collect less light, making them more prone to digital noise, especially in low-light conditions, and they generally have a lower dynamic range, meaning they struggle to capture detail in both very bright and very dark areas of a scene simultaneously.

For example, a modern smartphone camera might boast a high megapixel count, but its sensor is significantly smaller than that of a dedicated DSLR or mirrorless camera. Consequently, despite having the same megapixel count, the larger sensor of a professional camera will typically produce images with superior low-light performance, less noise, and richer tonal gradations. This distinction is vital for achieving truly beautiful photography and aesthetic quality, especially when venturing into challenging environments or aiming for professional-grade digital photography. Tophinhanhdep.com emphasizes understanding these technical nuances to truly appreciate and create high resolution images.

The Art of Digital Image Processing and Storage

Once light has been converted into digital data by the image sensor, the camera’s work is far from over. A sophisticated internal processing unit takes over, transforming this raw data into a usable and viewable image file.

In-Camera Processing and Data Management

The raw data generated by the sensor is essentially a digital blueprint of the light information. The camera’s internal processor applies complex algorithms to this data. This includes the demosaicing process for color reconstruction, noise reduction to minimize graininess, sharpening to enhance edges, and color correction to ensure accurate and pleasing hues. It also applies compression to create standard image file formats like JPEG, which are more manageable for storage and sharing. For professional digital photography, many cameras offer the option to save images in a “raw” format (e.g., .CR2, .NEF, .DNG). Raw files contain unprocessed sensor data, offering maximum flexibility for post-processing and photo manipulation without loss of quality, which is highly valued for creating graphic design elements or digital art.

This processed image data is then stored on a memory card. These “recording media” are essential for a digital camera’s operation. Tophinhanhdep.com recommends photographers always have sufficient capacity memory cards and consider carrying spares, especially when shooting a large volume of images or in situations where high-resolution files are critical. The speed of the memory card also plays a role in how quickly images can be written, impacting continuous shooting capabilities. A significant benefit of digital cameras is the instant feedback they provide, displaying the captured image directly on the camera’s LCD screen, allowing photographers to review and adjust their shots on the spot, feeding into continuous creative ideas and refining photo ideas.

Beyond Capture: Enhancing and Managing Your Images

The journey of an image doesn’t end with its capture. Post-processing and management are crucial steps in transforming a raw capture into a polished piece of digital art or a stunning wallpaper. Tophinhanhdep.com provides a suite of image tools designed to empower photographers and designers in this phase.

Our converters allow you to change image formats for different uses, while compressors and optimizers reduce file sizes without significant loss of quality, making images suitable for web use, backgrounds, or faster sharing. For photographers aiming to salvage or enhance older, lower-resolution images, our AI upscalers leverage artificial intelligence to intelligently increase image resolution and detail. Furthermore, the image-to-text tool can be invaluable for cataloging and searching large collections of stock photos.

These tools are not just about technical adjustments; they are integral to developing distinct editing styles and executing photo manipulation techniques. Whether you’re aiming for a moody, sad/emotional aesthetic or a bright, vibrant feel for nature photography, post-processing allows for creative expression that complements the initial capture. Tophinhanhdep.com encourages users to explore these tools to fully realize their visual design visions, transforming simple captures into graphic design assets or compelling digital art.

Essential Accessories and the Broader World of Photography

While the camera body and lens are the core, a range of accessories significantly enhances a photographer’s capabilities, adding convenience, stability, and expanding creative possibilities. Understanding these tools is part of mastering digital photography and producing diverse image inspiration & collections.

Powering Your Vision: Batteries and Stability

A digital camera is an electronic device, and as such, it cannot operate without power. Batteries are the lifeblood of your camera. Tophinhanhdep.com strongly advises ensuring your batteries are fully charged before any shoot, and carrying spare batteries and a charger, especially when traveling or embarking on extended beautiful photography expeditions. Unexpected battery drain can quickly cut short a creative session.

For many photographic scenarios, a tripod is an indispensable accessory. It provides a stable platform, eliminating camera shake and preventing “hand-motion blur,” which is particularly problematic with slower shutter speeds or longer focal lengths. Tripods are essential for shooting sharp night scenes, long-exposure abstract effects, using the self-timer for group photos, or when precise composition is paramount. They allow photographers to experiment with artistic techniques that would be impossible handheld, contributing to unique photo ideas and trending styles in photography.

Expanding Creative Horizons: Flashes, Straps, and Lenses

The built-in flash on many cameras is convenient, but an external flash unit offers significantly more power and flexibility. With an external flash that allows for angle adjustment, light can be bounced off walls or ceilings. This technique diffuses and softens the harsh light, creating more natural-looking illumination, reducing harsh shadows, and allowing for greater creative control over lighting, a crucial element in visual design and creative ideas.

For safety and convenience, a camera strap is a highly recommended accessory. Whether a neck strap or a hand strap, it prevents accidental drops, protecting your valuable equipment from damage.

Beyond the standard lens, conversion lenses can offer different perspectives without requiring a full lens change. A wide conversion lens can expand your field of view, ideal for capturing more of a scene, while a teleconversion lens magnifies distant subjects, similar to a telephoto lens, allowing for tighter framing. These additions can inspire new photo ideas and creative ideas for capturing nature or specific thematic collections. Furthermore, a good camera case protects your equipment from dirt, scratches, and bumps during transport, ensuring it remains in optimal condition for capturing beautiful photography for years to come.

Photography as an Art Form on Tophinhanhdep.com

Understanding the intricate mechanisms of how a camera captures an image empowers photographers to move beyond mere snapshots and into the realm of conscious creation. It allows for intentional choices about aperture, shutter speed, ISO, and lens selection, translating directly into the aesthetic and emotional impact of the final image.

At Tophinhanhdep.com, we celebrate this blend of science and art. Our platform serves as a comprehensive resource, offering not only the technical tools for image optimization and photo manipulation but also a rich wellspring of image inspiration & collections. From stunning wallpapers and diverse backgrounds to curated mood boards and insights into trending styles, we aim to ignite your passion for digital photography and visual design. Whether your interest lies in capturing the profound beauty of nature, exploring the depths of abstract forms, conveying powerful sad/emotional narratives, or simply mastering the craft of beautiful photography, Tophinhanhdep.com is your partner in transforming light into lasting visual masterpieces.

In essence, the journey of light through a camera is a fascinating blend of physics, chemistry (in film), and advanced electronics (in digital). From the initial bending of light by the lens to the final processing of pixels into a vivid image file, every step is a testament to human ingenuity. By understanding this journey, photographers can gain greater control over their craft, transforming simple observations into compelling visual stories and contributing to the vast and beautiful world of images available on Tophinhanhdep.com.