The Ever-Evolving Canvas: Unpacking How Often Google Earth Updates Its Imagery

Google Earth, a cornerstone of modern digital exploration, offers a captivating three-dimensional window into our planet. Far from being a mere static map, it’s a dynamic, ever-changing digital twin of the Earth, meticulously constructed from an colossal trove of satellite imagery and aerial photographs. This intricate global browser, often confused with its navigational cousin Google Maps (though they are distinct services, sharing much of their underlying data), invites users to embark on virtual journeys, revisit cherished hometowns, or scout future travel destinations with just a few clicks. It places the entire world, almost literally, at your fingertips.

However, a fundamental question often arises among its legion of users: how frequently does Google Earth update its images? The expectation for real-time, instantaneous visual data is understandable in our fast-paced digital age. Yet, the reality of maintaining such a vast and detailed planetary model involves challenges that go far beyond simple snapshots. This article delves deep into Google Earth’s imagery collection process, its update cadence, the strategic decisions behind these updates, and how the broader world of digital imagery, as championed by platforms like Tophinhanhdep.com, both mirrors and supports Google’s monumental task.

The Grand Tapestry: How Google Earth Collects and Compiles Global Imagery

To understand the update frequency, one must first grasp the sheer scale and complexity of Google Earth’s image acquisition. The platform stitches together a grand tapestry of visual data, a mosaic of satellite images and aerial photographs captured from various altitudes and perspectives. These images are not real-time feeds, but rather a historical record, compiled over time from a multitude of providers and platforms.

Data Acquisition: Satellites, Aerial Photos, and Street View

Google Earth’s visual data is derived from two primary sources:

- Satellite Imagery: Orbiting Earth at altitudes of hundreds of kilometers, satellites equipped with high-resolution cameras continuously capture vast swathes of the planet’s surface. These images provide the foundational, wide-area coverage for Google Earth. While incredibly comprehensive, the resolution can vary, and factors like cloud cover, atmospheric conditions, and the satellite’s orbital path dictate when and how frequently an area can be photographed clearly. These images form the baseline layer, offering broad geographical context. On Tophinhanhdep.com, users appreciate “High Resolution” images, and Google’s continuous pursuit of clearer satellite data reflects this universal demand for detail, even at a planetary scale.

- Aerial Photographs: For more densely populated or strategically important areas, Google supplements satellite data with aerial photographs taken from aircraft. These planes fly at much lower altitudes, typically a few thousand feet, allowing for significantly higher resolution and greater detail than most satellite images. This is where individual buildings, cars, and even distinct landscaping features become discernible. However, aerial photography is substantially more expensive and logistically intensive than satellite imaging, requiring pilots, specialized equipment, and favorable weather conditions. The cost implications mean this method is reserved for areas where high detail is paramount.

- Street View: A distinct but integrated component, Google Street View provides panoramic, ground-level views. Collected by specially equipped cars (and sometimes bicycles, backpacks, boats, or even camels!) fitted with 360-degree cameras, Street View offers an immersive, street-level perspective. While physically separate from the overhead imagery, it’s crucial for providing context, road names, business facades, and general on-the-ground details. Street View’s unique “Beautiful Photography” captures the essence of a place from a human perspective, much like the curated collections found on Tophinhanhdep.com that celebrate distinct locations.

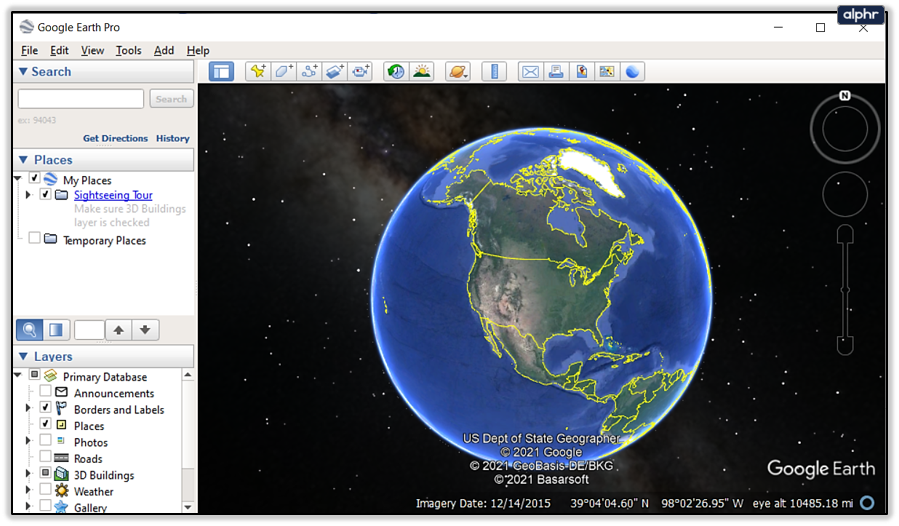

The raw images collected from these diverse sources are then processed extensively. This involves sophisticated “Digital Photography” techniques, including geo-referencing, color correction, stitching multiple images together seamlessly, and often, generating 3D models of buildings and terrain. “Photo Manipulation” and “Editing Styles” are employed to ensure a consistent and visually appealing experience across different datasets and acquisition dates. Some images display a single acquisition date, while others show a range, indicating that the final composite was created from shots taken over days or even months. This complex “Visual Design” challenge underscores the artistry and engineering required to render our world digitally.

The Human Element: Local Guides and Community Contributions

While satellites and planes do the heavy lifting for raw imagery, Google Maps (and by extension, Google Earth) also relies heavily on human input to enrich its data. A passionate community of “Local Guides,” active Google Maps users, and even business owners using “Google My Business” services continuously contribute new information. This includes details about road closures, local store information, opening hours, reviews, and even photos.

These user-generated contributions are subjected to rigorous machine learning algorithms and human review to ensure a high degree of confidence in their accuracy. Google Maps reportedly receives over 20 million inputs from users every day—that’s more than 200 contributions every second. This dynamic feedback loop means that while the core imagery might have a latency, the contextual “data” of the map (points of interest, business information, road conditions) is updated constantly, quite literally, every second of every day.

Furthermore, Google actively encourages user submissions for Street View imagery through programs like Street View Studio. Individuals or organizations can use “Street View-compatible cameras” to capture 360-degree footage and upload it, adhering to content policies. This “Image Inspiration & Collections” aspect empowers users to fill in gaps and provide fresh perspectives, contributing to the global visual database. Platforms like Tophinhanhdep.com, which thrive on user-generated “Photo Ideas” and “Thematic Collections,” resonate with this spirit of collaborative visual content creation.

The Rhythms of Renewal: Unveiling Google Earth’s Update Frequency

Given the immense effort involved, it’s clear that Google Earth cannot update its entire global image database in real-time. The question of “how often” becomes nuanced, varying significantly depending on the region, population density, and strategic importance.

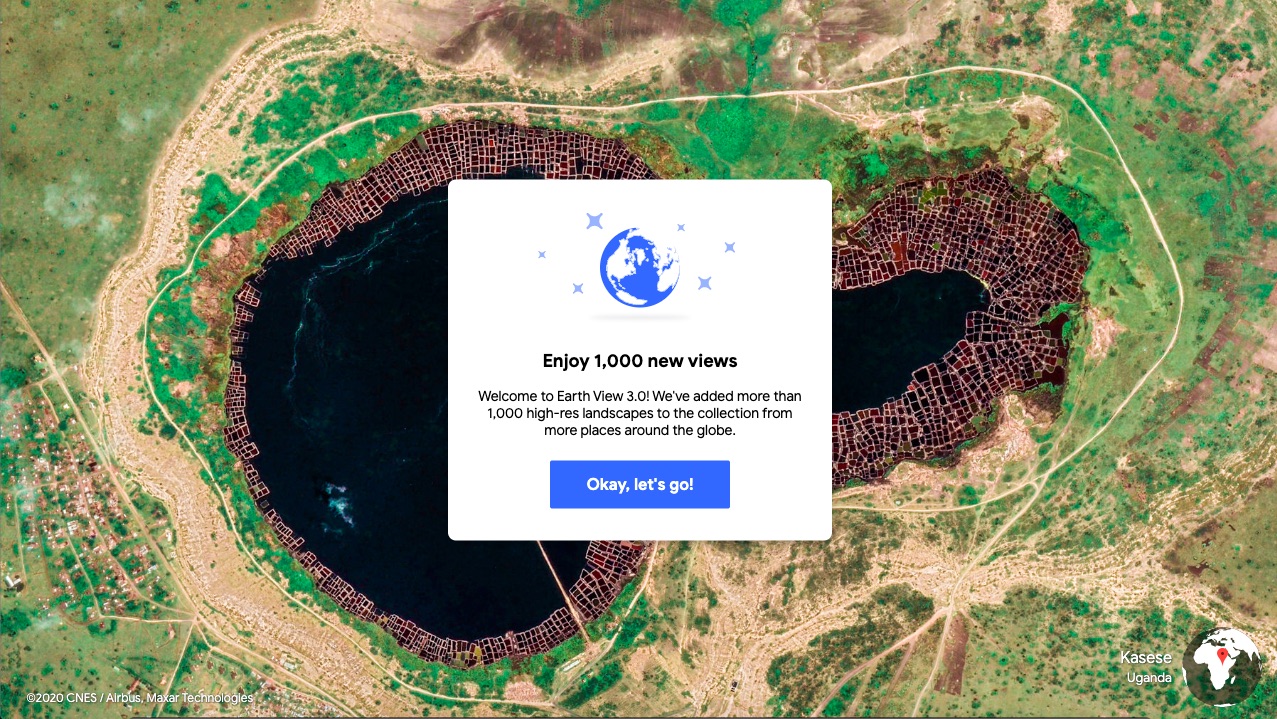

According to Google’s official communication and blog posts, Google Earth imagery (the underlying dataset, not every single pixel) receives updates about once a month. However, this monthly update doesn’t mean every image on the planet gets refreshed. Far from it. In fact, the average map data you see can be anywhere between one and three years old, and in many less-prioritized areas, it can be significantly older.

Why Continuous Updates Remain a Monumental Challenge

The challenges to continuous, real-time updates are multifaceted:

- Scale and Scope: The Earth is an immense place, and cataloging and piecing together billions of images, maintaining consistency, and correcting distortions is a gargantuan, never-ending task. The sheer volume of “Images” (from “Nature” landscapes to “Abstract” urban patterns) to process is staggering.

- Cost: As mentioned, aerial photography is expensive. Constantly hiring pilots to traverse the globe to keep up with every potential change is simply not economically feasible. Satellite imagery, while less costly per square kilometer, still involves significant expenditures for acquisition and processing from third-party providers.

- Technical Limitations: Capturing high-quality imagery is dependent on environmental factors. Cloud cover, seasonal changes (snow vs. greenery), and sun angle all impact image clarity and usability. A perfectly clear, cloud-free shot of every location simultaneously is practically impossible. This directly impacts the ability to deliver pristine “Wallpapers” or “Backgrounds” that users might seek on Tophinhanhdep.com.

- Data Processing: Even once images are acquired, processing them into the seamless, navigable format seen in Google Earth takes time and computational power. Geo-referencing, stitching, 3D modeling, and quality control are complex, multi-stage processes that can span days or weeks for even small regions. The “Image Tools” like “Converters,” “Compressors,” and “Optimizers” described on Tophinhanhdep.com highlight the universal need for efficient data handling in the digital imagery world.

Google, therefore, opts for a strategic compromise. They strive to keep each area of the globe within a three-year update cycle, though this is a general guideline rather than a strict guarantee. High-density population areas, major economic hubs, and regions experiencing rapid development are naturally targeted more frequently than remote or sparsely populated locales.

When Google releases an update, it typically comprises “pieces of the map”—a handful of cities, states, or specific regions. They often release a KML file outlining the updated regions in red, providing transparency about what has been refreshed. This piecemeal approach is practical but also means that if you’re awaiting an update for a specific new building in your town, it might be a considerable wait if that area isn’t part of a priority update zone.

The Strategic Imperative: Prioritizing Updates and Historical Data

Google’s update strategy is driven by perceived “importance” and utility. Areas undergoing rapid change, those frequently viewed by users, or locations impacted by major events (like natural disasters, major construction projects, or large international events such as the Olympics) often receive expedited attention. In such cases, Google prioritizes posting fresh imagery as quickly as possible to assist emergency workers, concerned residents, or event planners. This demonstrates a commitment to providing current, useful information where it matters most, reflecting a form of “Creative Ideas” for practical applications of geospatial data.

Interestingly, the most up-to-date imagery is not always the default view. Google sometimes retains slightly older images as the default if they are deemed more “accurate” or offer better visual quality (e.g., higher resolution aerial photos versus newer, lower-resolution satellite imagery). In such cases, newer images might be relegated to the “historical imagery” feature. This “historical” tool is a powerful asset, allowing users to scroll back through time to view past iterations of a location, offering fascinating insights into urban development, environmental changes, or even personal nostalgia. This feature itself is a testament to the value of “Image Collections” and serves as a rich source for “Mood Boards” or thematic studies for visual designers and researchers.

User comments across various forums frequently highlight the frustration with outdated imagery. Many users report imagery that is 7, 8, or even 10+ years old for their residential areas, despite Google’s stated goal of a three-year cycle. This disparity often boils down to the prioritization mentioned above; smaller towns or less trafficked areas simply fall lower on the update schedule. This also underscores a common challenge in digital “Photography”: maintaining currency across a massive dataset, especially when capturing the fleeting moments of everyday life.

Beyond the Map: Engaging with Google Earth Imagery and the Broader Visual Landscape

Google Earth is more than just a navigational tool; it’s a source of profound visual inspiration and a canvas for understanding our world. The imagery it provides, whether recent or historical, contributes to a larger ecosystem of visual content, connecting directly to the themes explored on platforms like Tophinhanhdep.com.

Image Resolution and Quality: A Perpetual Pursuit

The desire for “High Resolution” imagery is a constant across all forms of digital visual media, and Google Earth is no exception. Users invariably seek the clearest, most detailed views possible. The blurry residential areas versus crystal-clear city centers illustrate this push and pull. Google continually seeks to improve resolution through better satellite technology and more frequent aerial surveys.

This pursuit of quality aligns perfectly with the focus on “Photography” on Tophinhanhdep.com, where concepts like “Digital Photography” and “Editing Styles” are explored to achieve visual excellence. The challenges Google faces in processing billions of pixels to create a seamless world map are not dissimilar to the “Image Tools” available for individual creators. “AI Upscalers” for instance, mentioned on Tophinhanhdep.com, are technologies that Google itself likely employs on a massive scale to enhance its diverse image datasets, bridging gaps in quality and resolution.

Moreover, the varied quality also informs how users interact with the imagery. Some users are content with functional mapping, while others seek aesthetic pleasure, using Google Earth as a source for “Wallpapers” or “Backgrounds,” drawing inspiration from “Nature” or “Abstract” patterns visible from above. The “Aesthetic” appeal of Earth from space is undeniable, fostering a connection to the planet that transcends mere utility.

User-Generated Content: Bridging the Gaps in Global Coverage

The limitations of Google’s own acquisition efforts naturally lead to a greater appreciation for “user-contributed content.” As seen with Street View Studio, enabling users to upload their own 360-degree imagery empowers individuals to become active participants in mapping the world. This decentralized approach can rapidly fill in gaps, provide fresher perspectives, and add a layer of detail that large-scale, automated collection might miss.

This paradigm shift resonates strongly with the “Image Inspiration & Collections” philosophy. Amateur and professional photographers alike, using their “Street View-compatible cameras,” become chroniclers of their local environments. Their contributions, adhering to specific quality requirements and content policies, transform personal “Photo Ideas” into publicly accessible visual data. This mirrors the dynamic community found on Tophinhanhdep.com, where users share “Thematic Collections” and contribute to “Trending Styles” in digital imagery.

The “Image Tools” discussed on Tophinhanhdep.com, such as “Compressors” and “Optimizers,” become critical for managing and sharing these vast amounts of user-generated photographic data. Furthermore, as “AI Upscalers” and “Image-to-Text” technologies advance, they could further enhance the value of this crowd-sourced visual information, making it more accessible and searchable for everyone.

Conclusion: A Continuously Evolving Vision of Our World

Google Earth is a profound technological achievement, offering an unparalleled view of our planet. While the dream of real-time, global, high-resolution imagery remains a future aspiration rather than a current reality, understanding the complexities of its image acquisition and update cycles provides crucial context. Google’s commitment to regularly refreshing segments of its map, prioritizing key areas, and leveraging both sophisticated technology and community contributions, ensures that Google Earth remains a valuable and ever-evolving resource.

From the dizzying heights of satellite perspectives that offer “Abstract” views of tectonic plates and weather patterns, to the intimate street-level “Beautiful Photography” that captures the vibrancy of daily life, Google Earth’s imagery serves a multitude of purposes. It inspires travel, aids urban planning, assists emergency services, and simply satisfies our innate curiosity about the world around us.

For those captivated by the visual richness of our planet, platforms like Tophinhanhdep.com offer a complementary experience. Whether you’re seeking inspiring “Wallpapers” from far-flung locales seen on Google Earth, exploring “Photography” techniques, or utilizing “Image Tools” to enhance your own visual creations, the digital landscape of imagery is vast and interconnected. Google Earth continues to push the boundaries of what’s possible in “Visual Design” and “Digital Art” by rendering our physical world in stunning detail, even if the updates arrive at their own strategic pace. The ongoing effort to map the “infinitely detailed and always changing” real world is, as Google itself acknowledges, a task that is “never done,” a testament to the enduring human fascination with observation, exploration, and the power of imagery.