How To Know What Images You Need To Cite?

In today’s visually-driven world, where high-resolution photography, aesthetic wallpapers, and inspiring digital art are just a click away, the ease of access often blurs the lines of ownership and intellectual property. Whether you’re a student preparing an academic paper, a graphic designer creating new visuals, or a content creator curating thematic collections, understanding when and how to cite images is not merely a formality—it’s a cornerstone of academic integrity, ethical practice, and legal compliance. On Tophinhanhdep.com, we celebrate the vast spectrum of visual content, from nature photography and abstract art to sad/emotional images and beautiful photography. As we provide tools for image conversion, compression, optimization, and AI upscaling, we equally emphasize the responsible use of these assets. This comprehensive guide will demystify the process of image citation, particularly focusing on the widely adopted MLA 9th edition guidelines, ensuring you give credit where credit is due and avoid the pitfalls of plagiarism.

When to Cite Any Visual Content: The Fundamental Principle

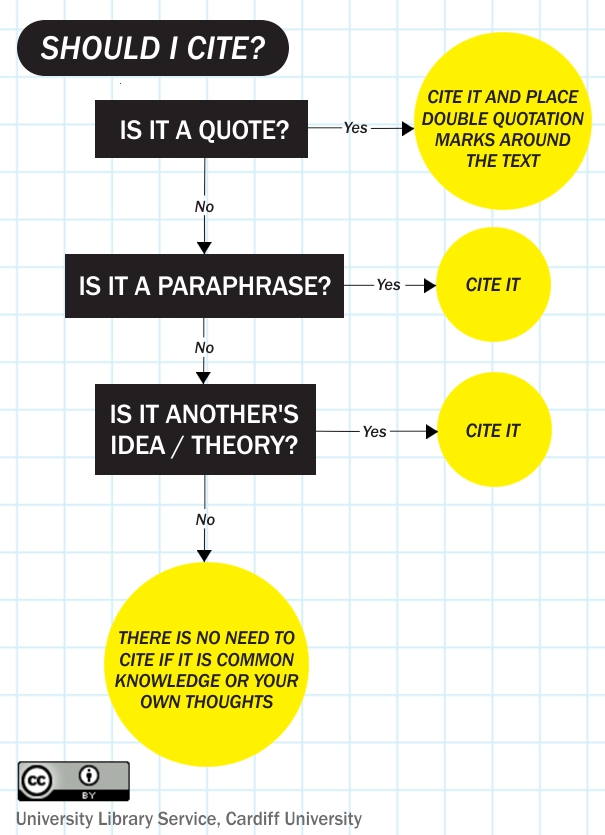

The act of citing is essentially an acknowledgment. It’s a way of saying, “This idea, these words, or this visual element did not originate with me; I’m borrowing it from someone else, and here’s who that someone is.” This principle applies universally, but with images and other visual content, its importance is often underestimated.

Identifying Work That Is Not Your Own

As a core rule, you must always cite any work that is not your original creation. The examiners, readers, or audience of your work must be in no doubt as to which elements are yours and which belong to someone else. This applies to ideas, text, figures, diagrams, and, crucially, images. On a platform like Tophinhanhdep.com, which offers a myriad of visual resources including wallpapers, backgrounds, aesthetic images, nature shots, abstract art, and emotional photography, it’s easy to download and use. However, the convenience of acquisition does not equate to ownership or permission for uncredited use.

You need to cite your source when you:

- Directly reproduce an image: This includes downloading a wallpaper, using a background image, or incorporating a beautiful photograph directly into your project. Even if you use image tools like compressors or optimizers from Tophinhanhdep.com, the core image remains someone else’s.

- Adapt or modify another author’s visual work: If you take a stock photo and apply extensive photo manipulation or use an AI upscaler, the original source often still requires attribution, depending on its licensing terms. The underlying creative work is not yours.

- Use factual information presented visually: This includes graphs, charts, infographics, or diagrams that illustrate data or theories that are not your original work.

- Refer to another artist’s or designer’s opinion or theory: Even if you’re not showing the actual artwork, discussing a specific piece of digital art or a graphic design trend attributed to a particular creator requires citation.

- Incorporate any visual content that is not your original work: This covers everything from clip art and icons to sections of a complex visual design or specific artistic elements.

The distinction is simple: if you didn’t create it entirely from scratch, or if you derived it from someone else’s creation, you need to acknowledge the source. This is vital for maintaining academic integrity and respecting the intellectual property rights of creators in photography, digital art, and visual design.

The Nuance of Common Knowledge in Visuals

While the rule “always cite work that is not your own” is clear, a common exception is “common knowledge.” But what exactly constitutes common knowledge when it comes to images? Generally, a fact or piece of information can be considered common knowledge when:

- It is widely accessible and easily verifiable from numerous sources.

- It is likely to be known by a large number of people.

- It can be found in general reference resources, such as dictionaries or encyclopedias.

For instance, a simple, generic photo of a globally recognized landmark like the Statue of Liberty might seem like common knowledge. However, a specific artistic photograph of the Statue of Liberty, taken by a particular photographer with unique lighting, composition, or editing style (e.g., a high-resolution, award-winning shot from a stock photo site), is decidedly not common knowledge. The individual creative effort and unique perspective embedded in that specific image make it attributable.

Consider the difference:

- Common knowledge (no citation needed for the concept, but perhaps for a specific image): “The Mona Lisa is a famous painting by Leonardo da Vinci.” (The fact itself).

- Not common knowledge (citation needed): A particular “beautiful photography” shot of the Mona Lisa taken from a specific angle under specific conditions by a contemporary photographer, or a digital art piece that heavily references it.

The boundaries of “common” versus “expert” or “unique” knowledge can be ambiguous, especially in specialized fields like digital photography or graphic design. If an image is presented as a unique piece of aesthetic, nature, or abstract art by a named creator, or if it comes from a specific collection (like those found under “Image Inspiration & Collections” on Tophinhanhdep.com), it almost certainly requires citation. When in doubt, it is always safer to cite the source than to risk plagiarism. Consult your instructor, supervisor, or a librarian if you are unsure.

Navigating Digital Image Sources: Quality, Verification, and Attribution

The internet is an unparalleled repository of visual content, offering everything from stunning wallpapers and diverse backgrounds to intricate digital art and creative ideas. However, this vastness also brings challenges, particularly concerning the reliability and proper attribution of images.

Critical Evaluation of Online Resources for Images

The internet provides access to millions of freely available, downloadable source materials, including countless images. However, it’s crucial to remember that there are no universal quality restrictions or automatic attribution mechanisms on the internet. You, as the user, need to exercise academic judgment about the visual material you find. This applies whether you’re sourcing images for a school project, personal blog, or professional visual design work.

When considering an image found online, especially for use in your projects (be it a presentation featuring aesthetic images, a website using high-resolution photography, or a mood board with trending styles), ask yourself:

- Who created it and why? Is the author, photographer, or artist clearly identified? If authorship of the electronic source is not given, question its reliability and whether it’s worth using. Reputable sources like stock photo sites (which often provide high-resolution photos with creator details) or established digital art platforms are generally more trustworthy than anonymous uploads.

- Is the work fact, opinion, or propaganda? Is it accurate/verifiable/current? While this applies more to informational content, for an image, consider if it’s depicting a verifiable event, an artistic interpretation, or a manipulated image designed to sway opinion. For instance, images used in photo manipulation projects might be explicitly altered, but if presented as factual, they need scrutiny.

- What is the purpose of the site where the image is hosted? Is it a personal blog, a news outlet, an educational institution, a stock photo agency, or an image inspiration gallery? The source’s purpose can indicate the image’s intended use and reliability.

Be especially careful if cutting and pasting or directly downloading work from electronic media. Never fail to attribute the work to its source. Even if you use Tophinhanhdep.com’s image tools like converters, compressors, or AI upscalers to process an image, this does not absolve you of the responsibility to attribute the original creation. The tool enhances the image; it does not transfer ownership. Always prioritize tracing images back to their original creators or reputable platforms to ensure proper attribution and legal use. For quality research, remember that not everything on the internet is free or available for unrestricted use. Subscription databases, curated stock photo libraries, and established art communities often provide quality, licensed content that expands your options beyond simple web searches.

Mastering MLA Citation for Images and Digital Media

When incorporating images into your work, particularly in academic or formal creative contexts, MLA (Modern Language Association) style is frequently required. The MLA 9th edition provides clear guidelines for citing various types of sources, including visual media. This section will guide you through the process, focusing on the specific requirements for images, photography, and digital art.

Essential Elements for In-Text Citations of Images

In MLA style, in-text citations serve to briefly point your reader to the more complete information available in your Works Cited list. For images and other non-textual figures, this typically means including a reference to the image creator or a shortened title directly in your text or caption.

When you incorporate an image into your paper, it’s generally labeled as a “Figure” (abbreviated as “Fig.”). Each figure should have a number, a caption, and then the citation information. The caption usually appears directly below the image.

Example of an In-Text Reference with a Caption: Fig. 1. Doe, Jane. Golden Hour at the Mountain Lake. Nature Shots Daily, 15 Oct. 2023, www.natureshots.com/golden-hour.

If you refer to the image within your prose, you would typically use the figure number: “The serene Golden Hour at the Mountain Lake (see Fig. 1) captures the ethereal beauty of dawn.”

For sources with page numbers (less common for standalone images but possible for images within a book or PDF), you would include the author’s last name and the page number in parentheses, placing the citation at the end of the sentence, before any punctuation. For media sources like films or podcasts that might contain a visual you’re referencing, you would include a timestamp. However, for most standalone images, the attribution resides primarily in the caption and the Works Cited entry.

Constructing Works Cited Entries for Visual Content

The Works Cited page provides the full bibliographic information for every source you’ve referenced. For images, the goal is to provide enough detail for your reader to locate the original visual. The general format for an online image is:

Creator’s Last Name, First Name. “Title of Image” or Description. Website Name, Day Month Year, URL.

Let’s break down various scenarios relevant to Tophinhanhdep.com’s content:

-

Standard Online Image (e.g., a wallpaper, aesthetic image, nature photography, or abstract art from a general website):

- Format: Creator’s Last Name, First Name. “Title of Image” or Description. Website Name, Day Month Year, URL.

- Example: Doe, Jane. Golden Hour at the Mountain Lake. Nature Shots Daily, 15 Oct. 2023, www.natureshots.com/golden-hour.

- Note: If the image lacks a formal title, provide a brief, descriptive phrase in place of the title (not italicized or in quotation marks).

-

Stock Photo (High-Resolution, Digital Photography):

- Format: Creator’s Last Name, First Name (if available). Title of Image. Stock Photo Site Name, URL.

- Example: Smith, John. Dynamic Cityscape at Dusk. Shutterstock, www.shutterstock.com/cityscape-dusk.

- Note: Stock photo sites like Shutterstock or Getty Images provide robust metadata, making these citations straightforward. Ensure you check the specific licensing terms, as attribution might be a condition of use even for free or purchased stock photos.

-

Image from a Database or Collection (e.g., museum, library of congress for historical photography):

- Format: Creator’s Last Name, First Name. Title of Work. Year of Creation. Collection/Museum Name, URL (if online).

- Example: Watkins, C. E. View on the Columbia, Cascades. 1867. The Met, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/262612.

- Example (no clear individual creator, from a library collection): “Parliament, Vienna, Austro-Hungary.” Ca. 1890. Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/item/2002708394/.

-

Graphic Design or Digital Art (e.g., from an artist’s portfolio site, Behance, ArtStation):

- Format: Artist’s Last Name, First Name. Title of Art. Year. Platform/Website, URL.

- Example: Chen, Wei. Abstract Geometric Fusion. 2022. ArtStation, www.artstation.com/artwork/abstractgeometricfusion.

- Note: For digital art or photo manipulation, the “creator” is the artist/designer.

-

Image without a Creator or Title (use a description):

- Format: Description of Image. Website Name, Day Month Year, URL.

- Example: Photograph of a serene forest path with sunbeams. Pexels, 20 May 2023, www.pexels.com/forest-path-image.

- Pro Tip: If a source (like “Agricultural Revolution” in a video) lacks an author but has a title, use the title. For images from time-based media, include a timestamp if the entire source is not being cited.

-

Citing an image from a print source (less common for the website’s focus, but good to know):

- Format: Creator’s Last Name, First Name. Title of Image. Year. Title of Book/Journal, by Author of Book/Journal, Publisher, Year, Page or Plate number.

- Example: Adams, Ansel. Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico. 1941. Ansel Adams: An Autobiography, by Ansel Adams, Little, Brown and Company, 1985, plate 12.

Remember that when using Tophinhanhdep.com’s image tools like AI upscalers, converters, or compressors, you are essentially creating a derivative version of an existing image. The original creator still holds the intellectual property for the base image, and proper citation remains paramount. The tool changes the format or resolution, not the authorship.

Beyond Citation: Ethical Engagement with Visual Content on Tophinhanhdep.com

Proper citation is more than just an academic requirement; it’s a fundamental aspect of ethical conduct and a demonstration of respect for the creators behind the myriad of images we encounter daily. This principle is especially vital in the dynamic world of visual design, digital photography, and creative content creation, where inspiration is often drawn from countless sources.

On Tophinhanhdep.com, we provide a diverse range of visual content—from wallpapers and backgrounds to aesthetic and nature photography, alongside tools for image manipulation and optimization. Our aim is to empower users with creative resources, but this empowerment comes with the responsibility of ethical usage.

Key Ethical Considerations and Quality Sourcing:

- Respect Intellectual Property: Every image, whether a high-resolution stock photo, a piece of digital art, or a beautifully captured moment, represents someone’s creative effort and skill. Respecting this means seeking permission where necessary and always providing appropriate attribution.

- Utilize Reputable Sources: While the open web offers many visuals, relying on established and reputable sources significantly streamlines the citation process and ensures legal compliance.

- Subscription Databases: As highlighted in the EHSS Library guide, quality research demands quality resources. Many educational institutions and professional organizations subscribe to databases offering licensed images, ensuring both quality and clarity regarding usage rights.

- Stock Photo Libraries: Platforms like Shutterstock, Adobe Stock, Pexels, and Unsplash are excellent sources for high-resolution images. They clearly delineate licensing terms (e.g., royalty-free, editorial use, attribution required), making it easier to use images correctly.

- Public Domain and Creative Commons: Understanding various Creative Commons licenses (e.g., CC BY, CC BY-NC) or identifying public domain images (where copyright has expired) is crucial. These licenses specify how an image can be used, shared, and adapted, often requiring attribution.

- Beyond “Free to Use”: Many images labeled “free to use” online still come with conditions, such as requiring attribution. Always click through to the original source and read the fine print before assuming unrestricted usage.

- The “Pro Tip”: When in Doubt, Cite: This advice cannot be overstated. If there’s any uncertainty about whether an image requires citation, or how to cite it, err on the side of caution and include a citation. This protects you from accusations of plagiarism and ensures that the original creator receives due credit.

- Image Tools and Originality: While Tophinhanhdep.com’s image tools (converters, compressors, optimizers, AI upscalers) can transform an image’s technical characteristics, they do not transfer original authorship. If you use an AI upscaler on a photograph you didn’t take, the original photographer still deserves attribution. These tools enhance utility; they don’t grant creative ownership.

By consciously engaging with these ethical guidelines, users of Tophinhanhdep.com can not only leverage our tools and diverse image collections (wallpapers, backgrounds, aesthetic, nature, abstract, sad/emotional, beautiful photography) but also contribute to a culture of respect and integrity within the broader visual and digital design community.

In conclusion, understanding what images you need to cite is paramount for academic honesty and ethical creation in the digital age. By diligently identifying non-original work, navigating the complexities of online resources, and mastering MLA citation techniques, you ensure that every visual you use is properly attributed. This commitment not only upholds the integrity of your own work but also honors the countless photographers, artists, and designers who enrich our world with their creative contributions. For all your image needs and tools, remember Tophinhanhdep.com is here to support your creative journey responsibly.