What Are Images in a Poem: Crafting Visuals and Emotions Through Language

Poetry, at its heart, is an art form that transforms the intangible into the palpable, the abstract into the concrete. While we typically associate “images” with visual media—photographs, illustrations, or digital art—in the realm of poetry, an image is a far more nuanced and profound creation. It is not merely a picture but a sensory experience, a vivid mental construct built from carefully chosen words, rhythms, and sounds. Just as Tophinhanhdep.com curates a diverse array of visual content, from stunning wallpapers and high-resolution photography to thought-provoking abstract art and mood-setting backgrounds, poetry crafts its own gallery of “images” within the mind of the reader, inviting them to see, hear, feel, taste, and smell the world anew.

The essence of poetic imagery lies in its ability to evoke, rather than merely describe. A poet doesn’t just tell you about a “beautiful sunset”; they weave words that conjure the hues of orange and purple, the crispness of the evening air, the whisper of the wind, and the lingering sense of awe. This act of imaginative creation shares a surprising kinship with the world of visual design and digital media. Think of how a graphic designer uses color, line, and composition to elicit a specific feeling, or how a photographer’s lens captures a fleeting moment with such precision that it tells a whole story. Poets, too, are designers and photographers of the soul, using the tools of language to compose intricate “visuals” that resonate deeply.

This article delves into the multifaceted concept of “images” within a poem, exploring how linguistic structure, evocative language, and thematic depth combine to create powerful mental and emotional landscapes. We will examine the core elements that define poetic imagery, draw parallels to the diverse visual content found on Tophinhanhdep.com, and illustrate how poets, much like digital artists and photographers, craft, refine, and optimize their creations for maximum impact. From the aesthetic appeal of a perfectly metered line to the emotional resonance of a well-placed metaphor, understanding poetic images opens up a richer appreciation for both the written word and the broader spectrum of creative expression.

The Poetic Canvas: Structuring Visions with Words

Every piece of art, whether a sprawling landscape painting or a minimalist abstract, relies on fundamental structural principles. In the digital world showcased on Tophinhanhdep.com, this might manifest as the meticulous arrangement of elements in a graphic design, the careful cropping in a piece of digital photography, or the thoughtful categorization of a thematic wallpaper collection. Poetry is no different. The “images” it creates are not spontaneous bursts of creativity but are carefully constructed within a framework of lines, stanzas, and rhythmic patterns. These structural choices act as the foundational canvas upon which the poet paints their mental pictures, influencing how the “image” is perceived, its emotional weight, and its overall aesthetic.

Lines, Stanzas, and the Architecture of Imagery

At the most basic level, a poem is built from lines and stanzas. A line is a single row of words, and a stanza is a group of lines, much like a paragraph in prose. These seemingly simple divisions play a crucial role in shaping the reader’s experience of a poetic image. A short line might create a sense of urgency, isolation, or a sharp, focused visual, akin to a close-up shot in photography that isolates a key detail from a busy background. Conversely, a longer line can evoke expansiveness, narrative flow, or a broader, more panoramic mental image, mirroring a wide-angle photograph capturing a vast natural landscape. The strategic placement of line breaks can emphasize certain words, create suspense, or introduce a subtle shift in meaning, guiding the reader’s eye and mind through the unfolding “visual.”

Stanzas, separated by extra space or blank lines, typically organize the poem’s thoughts, concepts, or narrative segments. Each stanza can be seen as a distinct frame or a new “visual background” within the poem’s larger narrative or emotional collection. For instance, a poet might dedicate one stanza to describing a tranquil nature scene, creating an “image” reminiscent of a serene nature wallpaper on Tophinhanhdep.com. The subsequent stanza might then shift to an internal emotional state, offering an “abstract image” of feeling, similar to how an abstract background can convey mood without explicit depiction. The separation between stanzas acts as a visual and conceptual pause, allowing the reader to process the preceding “image” before moving to the next, ensuring each “visual” segment contributes effectively to the overall “design” of the poem. The names for stanzas themselves—couplet (2 lines), tercet (3 lines), quatrain (4 lines), cinquain (5 lines), sestet (6 lines), septet (7 lines), octave (8 lines)—underscore this architectural precision, each form lending itself to different structural effects and visual compositions.

Rhyme, while not universal, is another powerful structural tool that shapes poetic images. When words contain corresponding sounds, often at the ends of lines, they create a “pleasurable echo” that unifies the lines. This sonic unity can enhance the visual cohesion of the “images” being presented, making them “sound right together.” Imagine an aesthetic wallpaper on Tophinhanhdep.com where complementary colors and symmetrical patterns create a harmonious visual experience; rhyme functions similarly in poetry, weaving together linguistic elements to form a cohesive, appealing whole. The absence of rhyme, as seen in free verse, offers a different kind of freedom, allowing the “images” to unfold more organically, unconstrained by strict sonic patterns, much like a candid digital photograph captures a moment without artificial posing.

The Rhythmic Pulse: Meter and Syllabic Stress as Visual Beats

Beyond lines and stanzas, the very words and syllables in a poem play a key role in forming its structure and, consequently, its “images.” Meter refers to the rhythm of a line, determined by the number of syllables and the pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables. This rhythmic pulse is akin to the beat in a song or the carefully chosen tempo of a video on Tophinhanhdep.com designed to evoke a specific feeling. Syllabic stress, in particular, is crucial. Consider the word “present.” Stressing the first syllable (PREH-zent) evokes an image of a gift or the current moment, while stressing the second (pre-ZENT) conjures the image of an action, the act of giving. This subtle shift in pronunciation fundamentally alters the mental image created.

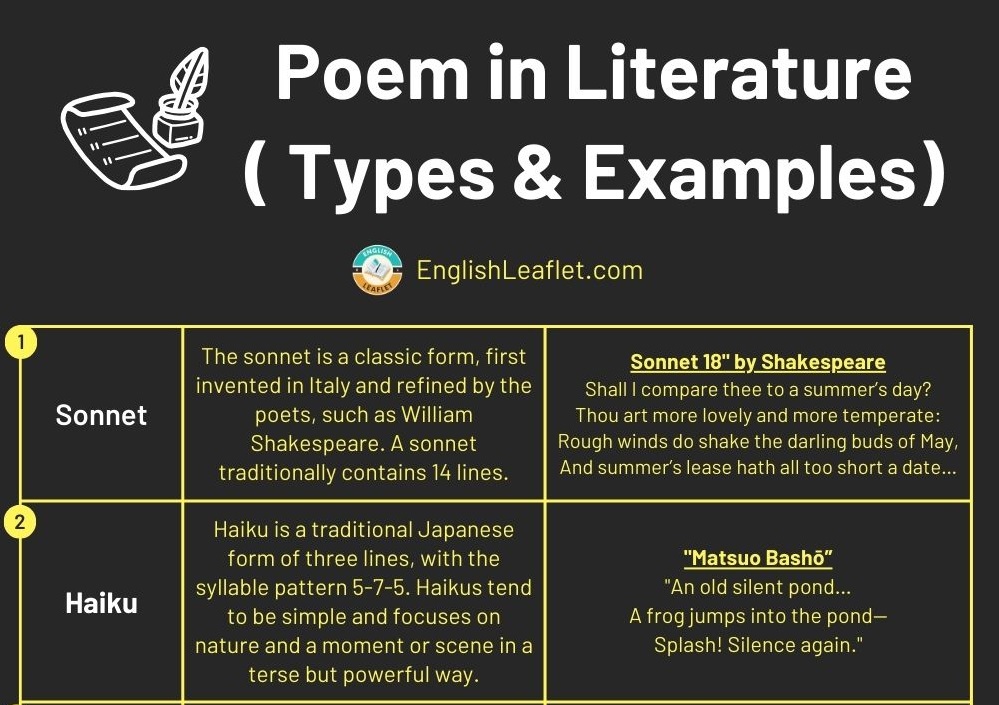

The consistent pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables helps create a rhythm that readers can follow, influencing the pace and mood of the poetic “images.” This pattern is broken into “feet,” groups of syllables usually containing one stressed and at least one unstressed syllable. The five most common types of feet—trochee (S+U), iamb (U+S), dactyl (S+U+U), anapest (U+U+S), and spondee (S+S)—each impart a distinct rhythmic feel. For instance, Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” uses trochaic meter, beginning with stressed syllables, creating a falling, somber rhythm that perfectly suits its dark, haunting “images.” Lord Byron’s “She Walks in Beauty,” on the other hand, employs iambic meter, starting with unstressed syllables, resulting in a rising, graceful rhythm that enhances the poem’s “beautiful photography” of its subject.

The number of feet per line further refines the meter: monometer (one foot), dimeter (two), trimeter (three), tetrameter (four), pentameter (five), hexameter (six), heptameter (seven), and octameter (eight). Iambic pentameter, famous in Shakespeare’s work, means five iambs per line, producing a natural, conversational rhythm that allows complex “images” and ideas to unfold with clarity and elegance. Much like a high-resolution image on Tophinhanhdep.com reveals intricate details, a poem’s meter brings precision to its sonic and emotional contours, ensuring that the “images” are delivered with optimal impact.

However, just as not all visual art adheres to strict grids or classical proportions, not all poetry employs rhyme or meter. Free verse, as exemplified by Langston Hughes’s “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” offers poets the freedom to write without these constraints. In free verse, the “images” are often shaped by the natural cadences of speech, by the visual arrangement of lines on the page, and by the sheer evocative power of the words themselves. This approach mirrors the versatility of digital photography and visual design, where artists can choose between structured compositions and more experimental, fluid forms to convey their creative ideas and capture unique “images.”

Painting with Words: Figurative Language and Sensory Details

While structure provides the frame, it is figurative language and sensory details that truly imbue poetic “images” with life, transforming mere descriptions into immersive experiences. On Tophinhanhdep.com, visual designers use graphic elements and digital art techniques to create captivating visuals, and photographers manipulate light and shadow to evoke specific moods. Poets wield words with similar mastery, employing a rich palette of linguistic tools to paint vibrant mental pictures and stir deep emotions in the reader. These techniques bridge the gap between abstract concepts and concrete sensations, making the invisible visible and the unspeakable felt.

Metaphor, Simile, and Personification: Bringing Abstract Concepts to Life

Some of the most potent tools in a poet’s arsenal for crafting “images” are metaphor, simile, and personification. These figures of speech don’t just describe; they transform and compare, forging unexpected connections that deepen the reader’s understanding and sensory engagement.

Metaphor directly equates two unlike things, stating that one is the other. It’s a bold stroke of imaginative painting, creating a fused “image” where previously distinct elements now share characteristics. For instance, saying “My love is a red, red rose” doesn’t just describe love; it is love. This single metaphor conjures a complex “image” of vibrant color, delicate petals, intoxicating scent, and perhaps even the prick of thorns, all instantly associated with the abstract concept of love. This is akin to a digital artist on Tophinhanhdep.com creating a composite image, blending elements to form a new, more profound visual statement that transcends its individual parts. The metaphor compresses a wealth of sensory and emotional information into a concise “visual.”

Simile, on the other hand, makes a comparison using “like” or “as,” drawing a clear, explicit link between two distinct entities. Phrases like “She walks in beauty, like the night / Of cloudless climes and starry skies” (Lord Byron) create a breathtaking visual. The woman’s beauty is not just described; it is compared to the serene, luminous image of a clear, starry night. This comparison evokes a sense of gentle radiance, vastness, and purity, far more vivid than a simple adjective could achieve. Similes are like pairing a central image with a carefully chosen “background” from Tophinhanhdep.com – the main subject is highlighted and enriched by the context of the comparison, adding depth and layers to the mental picture.

Personification gives human qualities or actions to inanimate objects or abstract ideas. This technique breathes life into the non-human world, making it relatable and emotionally resonant. When a poet writes of “the wind whispering secrets” or “the moon watching over the sleeping city,” they create dynamic “images” that engage the reader’s empathy and imagination. The wind isn’t just moving air; it has agency and intention. The moon isn’t just an celestial body; it’s a silent guardian. This humanization makes the poetic landscape feel alive, much like a compelling piece of digital art on Tophinhanhdep.com that imbues everyday objects with unexpected personality or emotion. These figures of speech are not just decorative; they are fundamental to how poetry constructs its unique brand of evocative “images,” translating the world into a language of feeling and visualization.

Sound and Emotion: Alliteration, Onomatopoeia, and Assonance as Sonic Imagery

The “images” in a poem are not solely visual; they are deeply intertwined with sound and rhythm. Poets manipulate the sonic qualities of language to create auditory “images” that enhance the overall sensory experience and emotional impact. This is where devices like alliteration, onomatopoeia, and assonance come into play, crafting a soundscape that complements the mental pictures.

Alliteration is the repetition of initial consonant sounds in words close to each other, such as “slippery slope” or “wild and woolly.” This repetition creates a musicality, a texture of sound that can draw attention to certain phrases and reinforce the “image” being presented. For example, a line heavy with ’s’ sounds might evoke the image of a soft, gentle breeze or a sinister, hissing presence. The sonic consistency adds a layer of aesthetic appeal, much like a well-designed graphic on Tophinhanhdep.com uses consistent visual elements or a specific color palette to create a harmonious and impactful composition.

Onomatopoeia refers to words that imitate the sounds they represent, like “buzz,” “crash,” “drip,” “pop,” or “whoosh.” This is perhaps the most direct way poetry creates auditory “images.” When a poet writes “the clatter of hooves” or “the hiss of the snake,” the words themselves replicate the sounds, instantly transporting the reader into the scene. These words bypass purely intellectual understanding and trigger a direct sensory response, making the “image” more immediate and immersive. This is akin to incorporating sound effects into a visual presentation to amplify the experience, making the digital image on Tophinhanhdep.com not just seen but also “heard” in the mind’s ear.

Assonance is the repetition of vowel sounds within words that are close to each other, like “flea” and “tree,” or “deep” and “sleep.” While less pronounced than alliteration, assonance creates an internal rhyming effect that can slow the pace, create a sense of longing, or contribute to a dreamlike quality. The soft, echoing vowel sounds can enhance the emotional resonance of a poetic “image,” much like a subtle background score in a film adds emotional depth to the visual narrative. It’s a delicate sonic brushstroke that adds nuance to the overall composition.

These sonic devices demonstrate that poetic “images” are a multi-sensory phenomenon. They engage not just the eyes of the mind but also its ears, fostering an experience that is richer, more immersive, and more emotionally charged. A poem’s ability to create these comprehensive sensory “images” is a testament to the poet’s skill in manipulating the very fabric of language, much like a digital artist layers textures and effects to create a truly captivating piece of digital art.

Thematic Collections and Emotional Landscapes in Poetry

The “images” within a poem are rarely isolated; they often coalesce around overarching themes, forming interconnected “collections” that define the poem’s core message or emotional landscape. Just as Tophinhanhdep.com organizes its vast library into thematic collections—Nature, Abstract, Sad/Emotional, Beautiful Photography—poetry, too, gathers its evocative “images” into thematic frameworks. These frameworks provide context, amplify meaning, and allow individual “images” to contribute to a larger, more resonant emotional or intellectual experience.

From Nature’s Grandeur to Inner Worlds: Diverse Poetic Themes

Poetry has long been a vehicle for exploring the vast spectrum of human experience and the natural world. This thematic breadth gives rise to an incredible diversity of poetic “images,” mirroring the varied “image inspiration and collections” one might find on Tophinhanhdep.com.

Nature Poetry, for instance, is replete with “images” that capture the grandeur and delicate intricacies of the natural world. Poems about trees, rivers, mountains, and skies evoke sensory details—the “cloudless climes and starry skies,” the “midnight dreary,” the “dust of snow.” These are literary equivalents of breathtaking nature wallpapers or high-resolution landscape photography. They invite the reader to visualize vibrant forests, serene lakes, or powerful storms, often imbued with symbolic meaning that reflects human emotions or philosophical ideas. Just as a photographer meticulously frames a shot of a sunset, a nature poet carefully selects words to paint a vivid mental picture of natural beauty, sometimes even creating a mood board of natural elements through language.

Conversely, many poems delve into inner worlds and abstract concepts. Poems about dreams, for example, explore the whimsical, sometimes terrifying, landscapes of the subconscious. “Climbing a Ladder” and “Flying” present “images” of fantastical journeys, defying gravity and logic, reminiscent of abstract or surreal digital art found in creative ideas sections. Other poems, like “It’s a Dream!”, craft “images” of crooked houses, bearded dogs, and dropping spiders—a collection of weird and offbeat visuals that might inspire an avant-garde digital artist seeking creative ideas for photo manipulation. These “dream images” are not factual but emotionally resonant, speaking to our subconscious fears and desires.

Then there are poems that directly address sad/emotional themes. “The Visit,” a wistful poem about missing grandparents, creates “images” of ghostly encounters within dreams, imbued with a deep sense of longing and memory. These “images” function as emotional backgrounds, setting a somber or reflective mood, much like a poignant black-and-white photograph or a melancholic aesthetic background on Tophinhanhdep.com can convey sorrow without explicit depiction. The poem’s “images” are not about objective reality but about the subjective experience of grief and remembrance, inviting the reader to share in that emotional landscape.

This thematic diversity underscores how poetic “images” are not confined to literal depictions. They can be realistic, fantastical, deeply personal, or universally resonant. Each poem, in its own way, becomes a “thematic collection” of carefully curated linguistic “images,” designed to evoke a specific experience or insight, akin to how Tophinhanhdep.com offers curated collections of trending styles or photo ideas.

Evoking Mood and Atmosphere: Poetry’s Emotional Wallpapers

Beyond conveying specific subjects, the collective “images” within a poem work synergistically to create a distinct mood and atmosphere, serving as the emotional “wallpaper” of the reader’s mind. The combination of structural choices, figurative language, and sonic elements determines whether a poem feels joyful, melancholic, suspenseful, or inspiring.

The rhythm and meter, for instance, can significantly contribute to the mood. A fast, bouncy rhythm might create an upbeat, humorous atmosphere, while a slow, heavy one can evoke sadness or solemnity. Consider the difference between a playful poem featuring onomatopoeic “bangs” and “pops” and a more reflective piece with elongated vowel sounds. The aesthetic impact of these choices is similar to how a bright, vibrant wallpaper on Tophinhanhdep.com instantly uplifts a space, while a darker, more muted background creates a sense of calm or introspection.

Figurative language also plays a critical role in shaping the emotional landscape. Metaphors and similes can draw surprising connections that challenge or affirm the reader’s feelings. Personification can make the environment feel empathetic or menacing, adding layers of emotional complexity to the “images” presented. Adjective poetry, which focuses on descriptive words, directly aims to create vivid “visual pictures” for the reader, enriching the emotional tapestry. These linguistic manipulations are akin to photo manipulation techniques used by digital artists on Tophinhanhdep.com to alter the perception and emotional resonance of an image, transforming a simple photo into a dramatic or dreamlike scene.

Furthermore, the overall theme itself contributes to the mood. Poems about dreams can range from whimsical to unsettling, each creating a unique atmospheric “background.” A poem about spring will likely evoke feelings of renewal and hope, while one about winter might conjure images of stark beauty or cold isolation. The “images” in the poem are not just descriptive elements; they are emotional anchors, guiding the reader through a carefully constructed feeling-scape. In essence, the poet acts as a curator of emotional experiences, selecting and arranging “images” to create an immersive atmosphere, much like Tophinhanhdep.com meticulously categorizes its “sad/emotional” or “beautiful photography” sections to help users find the perfect visual to match or evoke a particular mood. Through this masterful orchestration of language, poetry crafts emotional wallpapers that linger long after the last word is read.

The Poet as a Digital Artist: Crafting, Refining, and Optimizing Literary Images

In an era dominated by digital media, the act of creating “images” often involves a suite of specialized tools—converters, compressors, optimizers, and AI upscalers, as highlighted by Tophinhanhdep.com’s offerings. While poets don’t use software in the conventional sense, their creative process bears a striking resemblance to that of a digital artist or photographer. They meticulously craft their linguistic “images,” refine them through revision, and optimize every word for maximum impact and clarity. The poet, therefore, functions as a sophisticated “digital artist” of language, transforming raw ideas into polished literary masterpieces.

Precision and Resolution: Achieving Clarity in Poetic Detail

Just as a photographer aims for high-resolution images that capture every minute detail, a poet strives for precision and clarity in their linguistic “images.” This isn’t necessarily about literal description but about the sharpness of the emotional and sensory impact. High resolution in poetry means choosing words with such exactitude that they evoke the intended sensation or mental picture with minimal ambiguity.

Consider the role of adjectives. The Slideshare content emphasizes that adjectives are “describing words… used in poetry to create many different effects and visual pictures.” A single well-chosen adjective can transform a generic noun into a specific, vivid “image.” Instead of a “road,” a “roaring road” creates an auditory and potentially visual image of traffic. Instead of a “night,” a “dark, cold night” instantly establishes a mood and sensory detail. This meticulous selection of descriptive words is akin to a photographer adjusting focus and aperture to ensure every element in a beautiful photograph is crisp and clear. The “resolution” of a poetic image depends heavily on this linguistic precision, ensuring that the mental picture formed by the reader is as sharp and impactful as possible.

The concept of syllables and meter also contributes to this precision. By controlling the number of syllables and their stress patterns, poets can fine-tune the rhythm and flow of a line, ensuring that the “image” is delivered with the exact cadence and emphasis intended. This is similar to how a digital photography expert might adjust the “editing styles” of an image to bring out specific textures or highlights. The meticulous counting and arrangement of syllables, as seen in couplet poetry with its strict length requirements, ensures that the poetic “image” is not only beautiful but also structurally sound and economically presented. Every word, every sound, contributes to the overall clarity and impact, making the poetic “image” a high-resolution experience for the mind.

The Art of Revision: Poetic Editing and Manipulation

The journey from initial idea to finished poem is often one of extensive revision, a process akin to “photo manipulation” or applying sophisticated “editing styles” in digital art. Poets rarely get it perfect on the first try; they constantly re-evaluate, refine, and reshape their language to optimize the “images” they are trying to create. This involves a range of “image tools” – linguistic ones – to compress, expand, convert, and enhance.

Compression and Optimization: Poets are masters of conciseness. They often strive to convey complex ideas and vivid “images” with the fewest possible words, much like a “compressor” tool reduces file size without losing essential quality. Every word must earn its place, contributing to the overall aesthetic and meaning. This process of optimizing language removes clutter, sharpens focus, and ensures that the emotional and visual punch of the poem is delivered efficiently. A phrase like “a vast silence” can be more impactful than a lengthy description of quietude, achieving “high resolution” in a compressed form.

Conversion and Expansion (Image-to-Text / Text-to-Image): The very act of writing a poem is a form of “image-to-text” conversion. A poet observes a scene, feels an emotion, or imagines a concept – an internal “image” – and then translates that into words. The goal is for these words, in turn, to convert back into vivid “images” in the reader’s mind. The poem “Musical Exhaustion,” describing a dream of playing many instruments, takes an abstract dream experience and converts it into a tangible, if frenetic, textual “image” that allows the reader to “see” and “hear” the dream’s intensity. The poet selects the right vocabulary and poetic devices to facilitate this two-way conversion, ensuring that the initial inspiration is effectively re-imagined by the audience.

AI Upscaling (Imaginative Enhancement): While poets don’t use AI upscalers, their imaginative prowess performs a similar function. A poet can take a simple, mundane observation – a “dust of snow” (Robert Frost) – and through careful word choice and context, “upscale” its emotional and symbolic significance, transforming it into a moment of profound reflection or quiet beauty. The linguistic “upscaling” enhances the perceived “resolution” of the initial “image,” making it richer, deeper, and more impactful than its raw form. The careful arrangement of lines, the rhythm, and the subtle emotional cues elevate the ordinary into the extraordinary.

Photo Manipulation (Repetition and Creative Ideas): Repetition, as a poetic device, is a form of “photo manipulation.” By repeating a word, phrase, or sentence, poets can emphasize certain themes, ideas, or “objects,” creating patterns that resonate with the reader. “I’m car sick,” repeated throughout a poem, not only builds a pattern but intensifies the feeling, making the “image” of discomfort more pronounced and memorable. This is like a designer on Tophinhanhdep.com using a motif or recurring element to reinforce a brand message or create a cohesive visual identity. Each instance of repetition manipulates the reader’s perception, adding layers of meaning and reinforcing the central “image” or emotion.

Ultimately, the poet’s workstation is their mind and their tools are words. Through a rigorous process of creation, structural design, linguistic precision, and extensive revision, they craft “images” that resonate deeply, much like the curated collections of aesthetic, nature, and abstract art on Tophinhanhdep.com captivate their audience. The “images” in a poem are not static; they are dynamic, evolving constructs that live and breathe in the imagination, shaped by every syllable, every line break, and every carefully chosen metaphor. They remind us that true visual art can exist beyond pixels and paint, finding its most profound expression in the delicate dance of language.