What is an Afterimage: Exploring the Lingering Illusions of Vision

Our world is a tapestry of light, color, and form, interpreted by an intricate biological system – our eyes and brain. Yet, this sophisticated visual apparatus is not always a perfect, real-time recorder of reality. Sometimes, images linger, colors invert, and shapes persist even after the original stimulus has vanished. This fascinating phenomenon is known as an afterimage, or aftereffect, a captivating optical illusion that reveals the dynamic and adaptive nature of human perception. From the brief flash that etches itself onto your retina to the subtle illusions embedded in art and digital media, afterimages play a significant role in how we experience the visual world.

On Tophinhanhdep.com, where high-resolution images, stunning photography, and innovative visual design converge, understanding afterimages provides a deeper appreciation for the interplay between light, color, and perception. It sheds light on why certain aesthetic choices resonate, how visual tricks are created, and even how our visual system adapts to the myriad of visual content we consume daily, from vibrant wallpapers and abstract backgrounds to meticulously edited stock photos.

The Science Behind the Aftereffect: Rods, Cones, and Opponent Processes

The human visual system is a marvel of biological engineering, converting light into the rich tapestry of images we perceive. At the heart of this process are specialized light-sensitive cells located in the retina, a thin layer of tissue at the back of the eye. These cells, primarily rods and cones, are responsible for detecting light and initiating the complex cascade of nerve impulses that eventually reach the brain.

Retinal Fatigue and Color Receptors

The primary players in the afterimage phenomenon are the cones, photoreceptor cells that specialize in detecting color and fine details in bright light. Unlike rods, which handle low-light vision and peripheral perception, cones are responsible for our vibrant, high-definition view of the world. There are three types of cone cells, each most sensitive to specific wavelengths of light: red, green, or blue. Our perception of all other colors is a result of the brain interpreting the combined signals from these three types of cones.

The key to understanding afterimages lies in a concept called retinal fatigue. When you stare at a particular color for an extended period – typically 10 to 30 seconds – the specific cone cells sensitive to that color become “tired” or “fatigued.” Imagine a muscle that has been held in a contracted position for too long; it temporarily loses some of its strength. Similarly, these overstimulated cone cells become less responsive.

When you then shift your gaze to a neutral, typically white or gray, background, the fatigued cones do not fire as strongly as their non-fatigued counterparts. A white background is perceived when all three types of cones are stimulated equally. However, if, for example, your “red” cones are fatigued, they won’t send as strong a signal as the “green” and “blue” cones. This imbalance in the signals sent to the brain causes you to perceive the complementary color. This temporary imbalance is what creates the afterimage, and your vision quickly returns to normal as the fatigued cells recover. As simple experiments on Tophinhanhdep.com’s resources or similar educational platforms demonstrate, if you stare at a red object and then look away, you’ll likely see a green afterimage.

The Opponent Process Theory

While retinal fatigue explains how the cones become less responsive, the opponent process theory provides a framework for understanding why we see specific complementary colors. This theory, proposed by Ewald Hering in 1892, suggests that our color vision system processes colors in opposing pairs: red vs. green, blue vs. yellow, and black vs. white. These pairs are antagonistic; stimulating one color in a pair inhibits the perception of the other.

According to this theory, when cone cells sensitive to a particular color (e.g., red) are overstimulated and become fatigued, the opposing color in the pair (green) experiences a relative increase in activity. When you then look at a neutral surface, the non-fatigued, “opposite” cones fire more strongly, creating the perception of the complementary color. This sophisticated mechanism allows our visual system to adapt and maintain color constancy under varying lighting conditions, but it also gives rise to the intriguing illusions of afterimages. The dynamic interplay of these color pairs is a fundamental aspect of visual design and photography, principles extensively explored on Tophinhanhdep.com.

Unveiling the Two Types of Afterimages

Afterimages are not a singular phenomenon; they manifest in two distinct forms: negative and positive, each offering a unique insight into the workings of our visual perception.

Negative Afterimages: Complementary Colors and Lingering Forms

The more commonly experienced and often more striking type is the negative afterimage. As the name suggests, the colors of a negative afterimage are the complementary colors of the original image you were fixating on. If you stare at a bright red object and then close your eyes or look at a white wall, the afterimage will appear green. Similarly, a blue object will produce a yellow afterimage, and black will appear as white, and vice versa.

This effect is a direct consequence of the retinal fatigue and opponent process theory described earlier. The overstimulated cone cells for a particular color become desensitized, allowing the opposing color channels to dominate when the visual input shifts to a neutral background.

Many popular visual illusions and art pieces leverage negative afterimages to create astonishing effects. Tophinhanhdep.com, with its vast collection of aesthetic images and digital art, offers numerous examples where artists play with color inversion to create captivating experiences. Consider the classic “Beyoncé, Afterimage” demonstration, where staring at a distorted, color-inverted image of a celebrity for 30 seconds, particularly a small white dot on her nose, and then closing your eyes, reveals a lifelike, naturally colored portrait. The unnatural colors in the original image fatigue your cone cells in such a way that when you close your eyes, the complementary colors perceived create a more realistic depiction.

Another famous example is the “lilac chaser” illusion. When you stare at the black cross in the center of an animation featuring a circle of fading pink dots, a green dot appears to chase around the circle. Intriguingly, if you stare long enough, the pink dots themselves may even start to disappear. The “green” dot is a negative afterimage: as each pink dot vanishes, the fatigued cone cells for pink create a momentary perception of its complementary color, green, in that spot. Because the “chaser” moves fast enough, these brief afterimages combine to create the illusion of a continuously moving green circle. The disappearance of the pink dots, however, introduces another phenomenon known as the Troxler effect, where unattended peripheral images fade when focus is maintained on a central point. These kinds of dynamic visual puzzles are excellent examples of the “creative ideas” and “trending styles” that visual designers often explore, and Tophinhanhdep.com provides a platform for discovering and creating such engaging content.

Positive Afterimages: The Flicker of Reality and Motion Perception

In contrast to negative afterimages, positive afterimages appear in the same colors as the original stimulus. They are generally much shorter in duration, typically lasting only a fraction of a second, whereas negative afterimages can persist for several seconds.

Positive afterimages are essentially the direct continuation of the sensory activity after the stimulus has ceased. When a very bright light, like a camera flash, blazes for an instant, that annoying, flash-shaped light that lingers in your vision for a moment is a positive afterimage. It occurs because the photoreceptor cells remain active for a very brief period after the light source is gone, continuing to send signals to the brain that correspond to the original stimulus.

While fleeting, positive afterimages play a crucial, often unnoticed, role in our daily visual experience, particularly in the perception of motion. Consider the magic of movies. The average human eye can detect motion at around 75 frames per second (fps). However, most traditional movie theaters project films at just 24 fps. Why doesn’t a movie look choppy or like a series of still images? This smooth perception of motion is partly attributable to positive afterimages, working in conjunction with the phi phenomenon (the illusion of movement created when visual stimuli are presented in rapid succession).

After each frame flashes on the screen, a positive afterimage maintains that image in your eyes for a split second. This brief persistence bridges the gap between individual frames, making the sequence appear as continuous motion. While the phi phenomenon is the primary driver of perceived motion in film, positive afterimages contribute to the seamlessness, preventing the distinct “flickering” effect seen in very old, low-frame-rate silent films (around 16 fps). The digital photography and high-resolution imaging content available on Tophinhanhdep.com, when presented in sequences, also benefits from this fundamental aspect of human vision, enabling animated graphics and video clips to flow smoothly.

Experiencing Afterimages: Simple Experiments and Iconic Illusions

The beauty of afterimages lies in their accessibility; anyone can experience them with simple experiments. These visual tests not only provide an intriguing glimpse into our own visual system but also serve as foundational concepts for visual design and art, as showcased in the “photo ideas” and “creative ideas” sections of Tophinhanhdep.com.

DIY Experiments for Visual Discovery

Several straightforward experiments allow you to observe afterimages firsthand, similar to those found in educational resources or visual experiment pages. These simple exercises highlight the principles of retinal fatigue and complementary colors:

- The Colored Square Test: Focus intently on a small, brightly colored square (e.g., a vibrant red or green) for about 15-30 seconds, trying not to blink. Then, quickly shift your gaze to a plain white or neutral-colored surface. You should see a negative afterimage of the square in its complementary color. Tophinhanhdep.com’s extensive collection of abstract backgrounds and colorful wallpapers provides excellent material for such experiments.

- The Moving Circle Variation: Repeat the above experiment, but this time, follow a small moving circle within the colored image for the same duration. When you switch to a white background, you might find the afterimage to be less vivid or even absent. This is because your eyes are constantly moving, preventing any single set of cone receptors from becoming overly fatigued by a particular color in one spot. This demonstrates the localized nature of retinal fatigue.

- The Monocular Afterimage: This experiment uses one eye to focus on a colored image. For instance, close your right eye and, with your left eye, stare at a colored square for 15 seconds. Then, shift your left eye to a white background, and while still looking with your left eye, quickly open your right eye and compare the perception. The afterimage will predominantly be seen by the eye that was fixating, confirming that the fatigue occurs at the retinal level within the eye itself, rather than solely in the brain’s higher processing centers.

These experiments are not just fun visual tricks; they underscore the physiological basis of our perception, a concept often explored in digital art and visual design to create more impactful and interactive experiences.

Famous Afterimage Illusions

Beyond simple colored shapes, many iconic illusions harness the power of afterimages to create profound or surprising visual effects. These examples demonstrate how understanding afterimage principles can be applied to creative visual content, aligning with the “image inspiration & collections” found on Tophinhanhdep.com:

- The Jesus Illusion: Stare at the four black dots in the center of a black and white image of Jesus (often depicted in a negative, almost ghostly appearance) for 30-60 seconds. Then, quickly close your eyes and look at a bright light source, like a lamp or a sunlit window. You will typically see a white circle containing a clear, naturally colored image of Jesus. The black and white image, designed with specific contrasts, fatigues the opposing color receptors in a way that, upon looking at a bright field, the afterimage reveals the positive, natural-looking image.

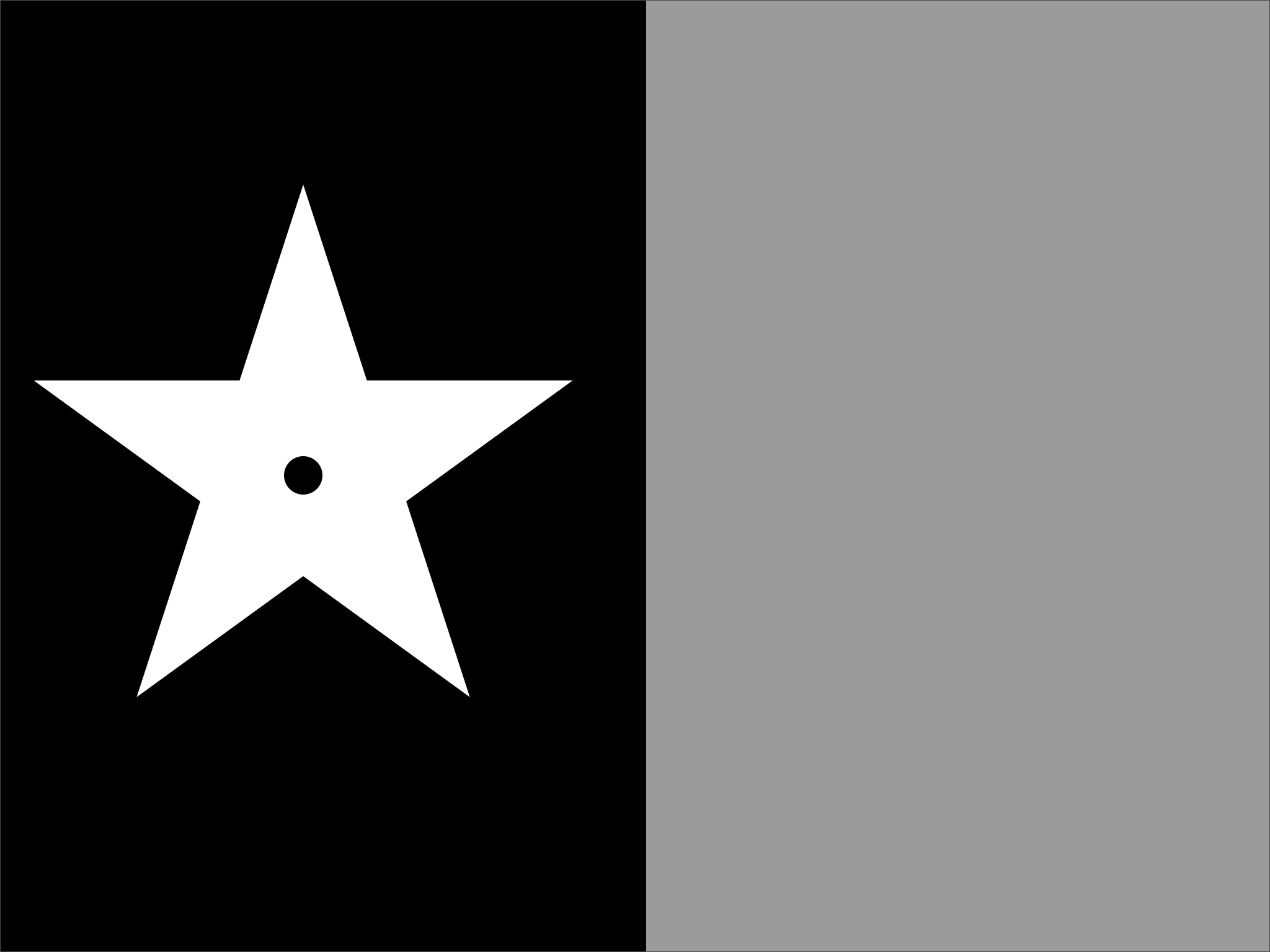

- Historical Figures and Flags: Similar illusions exist for famous figures like Che Guevara or national flags (e.g., the US or Italian flag). These images are often presented in distorted or color-inverted forms. By fixating on them for a period and then shifting to a white surface, the brain processes the complementary colors, revealing the familiar, correctly colored image of the person or flag. These are classic examples of how photo manipulation and graphic design can exploit visual perception.

- The Girl Illusion: Stare at a small red dot on the nose of an unnaturally colored (e.g., magenta and cyan) portrait of a girl for 30 seconds. Then, quickly look at a white ceiling or wall and blink rapidly. The distorted colors will invert, revealing a surprisingly vivid and naturally colored image of the girl. This is a powerful demonstration of how our brain “corrects” for color imbalances through afterimage formation.

- Color City and Castle: These illusions typically involve black and white images of cityscapes or castles with a single, often red or black, dot for fixation. After staring for a set time (e.g., 15 seconds), shifting your gaze to a white background makes the black and white image appear in full, vibrant color. These examples highlight the brain’s tendency to fill in missing information based on fatigued photoreceptors, making the monochromatic scene burst into an imagined spectrum.

These visual puzzles are not merely curiosities; they are foundational elements of visual literacy, demonstrating the subtle yet profound ways our eyes and brain construct reality. For creators of beautiful photography, digital art, and graphic design on Tophinhanhdep.com, these principles offer endless avenues for generating creative ideas and engaging viewers at a deeper perceptual level.

Adaptive Mechanisms and the Dynamics of Perception

The traditional explanation for afterimages, focusing solely on retinal fatigue, provides a good starting point, but newer research suggests a more dynamic and complex interplay of “adaptive mechanisms” within the brain. This perspective moves beyond passive receptor “tiredness” to consider active neuronal adjustments.

Beyond Fatigue: Neuronal Adaptation

Some theories propose that afterimages are not just a result of resource depletion in cone cells but are indicative of rapid adaptive mechanisms at play throughout our neural networks. Imagine the brain constantly trying to “make sense” of incoming visual data. If there’s a prolonged presence of a specific color, say an overwhelming amount of red, the visual system might infer that the source of light itself is red, rather than the objects being inherently red. To accurately perceive the true colors of objects, the system needs to compensate for this perceived “red” bias in the lighting. This compensation involves neurons quickly adapting to adjust how they process and route visual information.

This hypothesis leads to a counter-intuitive prediction: afterimages should fade quickly if the brain is given “grounds” to believe its current adaptations are faulty. In other words, if conditions change such that the visual system realizes its compensatory “corrections” are no longer needed, it should rapidly reverse them. This implies a more active, inference-driven process rather than just passive recovery from fatigue.

Fast vs. Slow Adaptation in Afterimage Erasure

Recent experiments have explored this idea by measuring the vividness of afterimages over time under different conditions. For instance, subjects might view natural scenes filtered through a strong green filter for 12 seconds, inducing a pink afterimage (pink being the complementary color of green). The vividness of this pink afterimage is then measured after varying intervals (e.g., 0ms, 200ms, 400ms, 800ms) under two conditions: either viewing a blank white screen or viewing full-color natural scenes.

The results are quite telling. When subjects stared only at a blank white background, the intensity of the pink afterimage remained relatively constant, consistent with the idea that unchallenged afterimages persist. However, when subjects were briefly presented with full-color photographs (even for as little as 200ms), the afterimages faded rapidly, losing more than 30% of their initial vividness. With longer exposure to full-color images, the decay was even greater, reaching about 50% clearance within less than a second. This demonstrates a “fast adaptive mechanism” at work: the brain quickly readjusts its perceptual “green-removal” adaptations when confronted with evidence (full-color images) that those adaptations are no longer appropriate.

Interestingly, experiments also showed that even a barrage of full-color images couldn’t clear more than an average of 50% of the afterimage, no matter how long the exposure. This suggests that while fast adaptive mechanisms are crucial for rapid corrections, there might also be a “slow, more robust part” of the afterimage that is harder to remove quickly. This implies a dual system of adaptation: fast mechanisms that allow for quick adjustments to perceived lighting distortions (helping us “see” better by compensating for overly green, dark, or light scenes) and slower mechanisms that provide a more stable, underlying perceptual framework. This sophisticated interplay of adaptation highlights the brain’s incredible capacity to interpret and stabilize our visual world, a process deeply relevant to understanding how we perceive intricate details in high-resolution photography and diverse aesthetic images on Tophinhanhdep.com.

Afterimages in the Digital Age: Relevance for Tophinhanhdep.com’s Visual World

The study of afterimages, though rooted in the biological mechanisms of human vision, has profound implications for the creation, appreciation, and manipulation of visual content in the digital era. For a platform like Tophinhanhdep.com, which specializes in “Images (Wallpapers, Backgrounds, Aesthetic, Nature, Abstract, Sad/Emotional, Beautiful Photography),” “Photography (High Resolution, Stock Photos, Digital Photography, Editing Styles),” “Image Tools (Converters, Compressors, Optimizers, AI Upscalers, Image-to-Text),” “Visual Design (Graphic Design, Digital Art, Photo Manipulation, Creative Ideas),” and “Image Inspiration & Collections (Photo Ideas, Mood Boards, Thematic Collections, Trending Styles),” understanding afterimages adds a critical layer to visual literacy and creative practice.

Enhancing Visual Appreciation and Photography

On Tophinhanhdep.com, where users explore a vast array of wallpapers, backgrounds, and beautiful photography, afterimages remind us that perception is not passive. A vivid nature scene, an abstract design, or an emotionally charged image doesn’t just present itself; our visual system actively interprets it. Photographers, for instance, can leverage an understanding of color theory and aftereffects in their “editing styles” to create images that subtly guide the viewer’s eye or produce specific emotional responses. High-resolution photos, with their intricate details and rich color palettes, can be designed to maximize or minimize potential afterimage interference, ensuring the intended visual message is conveyed. The choice of complementary colors in a composition, or the strategic use of high contrast, can influence how a subsequent image is perceived, adding depth to the “aesthetic” and “thematic collections” available.

Informing Visual Design and Digital Art

For “Visual Design” and “Digital Art” content on Tophinhanhdep.com, afterimages are not just a quirk of vision but a potential tool. Graphic designers and digital artists can intentionally incorporate principles of afterimages into their “creative ideas” and “photo manipulation” techniques. The “lilac chaser” illusion is a prime example of digital art using afterimage principles to create dynamic, moving effects from static images. By understanding how the eye fatigues and perceives complementary colors, designers can craft logos, advertisements, and interactive media that leave a lasting impression or create a sense of movement and vibrancy, even where none physically exists. This knowledge directly contributes to more effective “mood boards” and “trending styles” that resonate with the human perceptual system.

The Role of Image Tools and Inspiration

While “Image Tools” like converters, compressors, optimizers, and AI upscalers primarily focus on the technical aspects of image processing, the ultimate output is always subject to human perception. An image upscaled by AI to achieve stunning high resolution will still be viewed through eyes prone to afterimages. Understanding these visual phenomena can inform the development of tools that better account for human perception, perhaps even optimizing images to reduce unwanted aftereffects or enhance desired visual outcomes.

Furthermore, afterimages serve as a profound source of “Image Inspiration.” The idea that our minds can conjure vivid, color-inverted images from mere sustained gaze opens up new avenues for “photo ideas” and artistic experimentation. Exploring how different color combinations and durations of exposure create unique aftereffects can spark new “creative ideas” for visual storytelling and abstract art, influencing the diverse collections found on Tophinhanhdep.com.

In conclusion, afterimages are much more than simple optical illusions; they are a window into the dynamic, adaptive, and often surprisingly subjective nature of human vision. From the basic biology of our retinal cones to the complex adaptive mechanisms of our brain, these lingering visuals remind us that what we see is a constantly constructed reality. For creators and connoisseurs of visual content on platforms like Tophinhanhdep.com, an appreciation for afterimages enriches our understanding of color, light, design, and the captivating power of the human eye. And for the rare individuals who experience heightened and prolonged afterimages, known as palinopsia, scheduling an appointment with an eye doctor is crucial, underscoring that while afterimages are generally a normal part of vision, extreme instances warrant professional attention.