The Genesis of Pixels: Unraveling When the First Digital Image Was Created

In an era dominated by instantaneous digital photography, high-resolution imagery, and a seemingly endless wellspring of visual content on platforms like Tophinhanhdep.com, it’s easy to overlook the revolutionary origins of the digital image. What we now take for granted—the ability to capture, transmit, manipulate, and share images with unprecedented ease—was once an unimaginable concept, a frontier pushed by visionary scientists and engineers. This journey, beginning with abstract theories in the Victorian age and culminating in the ubiquitous pixelated world we inhabit, is a testament to human ingenuity.

Tophinhanhdep.com thrives on the rich ecosystem of digital images, offering everything from stunning wallpapers and diverse backgrounds to intricate digital art and powerful image tools. Yet, none of this would be possible without the foundational breakthroughs that first converted light into data. From aesthetic nature photography to abstract sad/emotional collections, the very essence of Tophinhanhdep.com’s offerings traces back to pioneers who dared to ask, “What if pictures could be seen by machines, and shared across distances?” Understanding “when was the first digital image created” is not merely a historical exercise; it’s an exploration of the roots that nourish the vast digital visual landscape of today.

The Dawn of Digital Vision: Conceptualizing Images as Information

The concept of transforming a visual scene into discrete pieces of information, transmittable and reconstructible, predates the computer age by decades. It required an intellectual leap to imagine that an image, traditionally rendered by light and chemistry, could instead be an electrical pattern, a series of signals.

Victorian Visions: Shelford Bidwell’s Telephotography (1880)

Long before computers became household names, the seeds of digital imaging were sown in the late 19th century by British researcher Shelford Bidwell. In 1880, Bidwell, a specialist in selenium, conceived a remarkable idea: to break a picture down into pure information and transmit it as an electronic signal. His pioneering work laid the theoretical and practical groundwork for sending images down a wire, a precursor to today’s lightning-fast data transfers.

Bidwell’s experiments hinged on the peculiar properties of selenium. He discovered that when light struck a selenium cell, its electrical resistance would vary. Integrated into a simple electrical circuit powered by a battery, a selenium cell would allow greater or lesser currents to flow depending on the intensity of the light hitting it. This meant that Bidwell could effectively translate varying light levels into fluctuating electrical patterns, akin to a Morse code-like intermittent signal. This fundamental insight—the conversion of light intensity into an electrical value—is at the heart of all modern digital image sensors.

To demonstrate his revolutionary concept, Bidwell constructed two ingenious machines: a transmitter and a receiver. He then created simple black-and-white silhouettes of a butterfly and a horse, images that would become the first examples of “telephotography.” His transmitting machine meticulously scanned each picture line by line. As it passed over a transparent area, light was allowed through to the selenium photocell, which generated an electrical signal. Conversely, when it scanned an opaque part, the light was interrupted, and no signal was generated. This stop-start electrical current, mirroring the visual information, was then sent down a telegraph wire to his receiving machine.

The receiver reversed this process. It contained a piece of paper soaked in potassium. The incoming electrical signal reacted chemically with the potassium, effectively “burning” an exact replica of the original image onto the paper, line by line. Bidwell had used electricity to create a precise duplicate of his hand-drawn pictures across a distance. This was an astonishing achievement: he had transformed an image into digital information and found a method to transfer it to another location, making it shareable.

While Bidwell’s “telephotography” apparatus was an impressive leap, it did not immediately take off as a widespread technology. Its practicality was limited by the nascent state of electronics and the labor-intensive process. However, his vision profoundly influenced subsequent generations of researchers and inventors. His work validated the idea that images could be dissected into data, transmitted, and reassembled, setting the stage for the massive shift from chemical photography to the digital images that now populate Tophinhanhdep.com in myriad forms, from intricate digital art pieces to vast collections of high-resolution stock photos. The foundational idea of “sending images down a wire” has evolved into the instant sharing capabilities of today’s internet, a core function of visual platforms worldwide.

The Transformative Question: Russell Kirsch and the First Scanned Digital Image (1957)

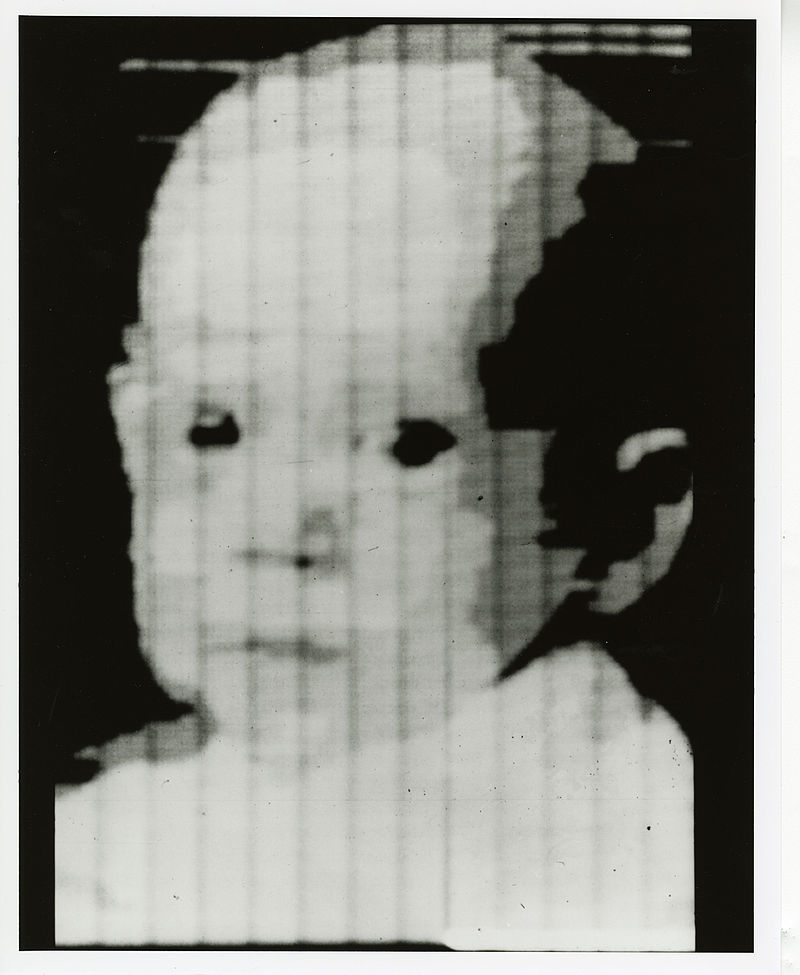

While Bidwell conceived the idea of digital transmission, the true dawn of the digital image as we recognize it today—a pixelated representation stored and manipulated by a computer—arrived in 1957. The catalyst was a profound question posed by computer pioneer Russell Kirsch at the U.S. National Bureau of Standards (NBS), now known as the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST): “What would happen if computers could look at pictures?” This inquiry ignited a revolution in information technology, laying the groundwork for virtually every digital imaging technology we use today.

Kirsch and his colleagues at NBS were at the forefront of early computing, having developed the nation’s first programmable computer, the Standards Eastern Automatic Computer (SEAC). Recognizing the immense potential of computers to process visual information, they embarked on a groundbreaking project. Their innovation involved creating a rotating-drum scanner, an invention by NIST itself, coupled with sophisticated programming that enabled images to be fed directly into the SEAC computer. This was the critical step: converting an existing analog (physical) image into a digital format that a computer could understand and store.

The very first image to be scanned and converted into a digital file was a modest black-and-white photograph: a head-and-shoulders shot of Kirsch’s then three-month-old son, Walden. The resulting digital image was remarkably small by today’s standards—a mere 5 centimeters by 5 centimeters and composed of only 176 pixels on each side. It was grainy, ghostlike, and a far cry from the multi-megapixel digital snapshots users enjoy today on Tophinhanhdep.com. Yet, this humble image of baby Walden Kirsch was an “Adam and Eve” moment for all subsequent computer imaging.

Its significance cannot be overstated. From this singular, grainy image sprang an entire universe of applications: satellite imaging, which relies on digital capture and processing to map our planet; CAT scans, a cornerstone of modern medical diagnostics that build digital 3D models from cross-sectional X-ray images; the ubiquitous bar codes on packaging, which are digital representations of product information; and the entire field of desktop publishing, which revolutionized graphic design by allowing text and images to be digitally integrated and prepared for print. Fundamentally, Kirsch’s work paved the way for digital photography itself.

The profound impact of Kirsch’s achievement was recognized in 2003 when the editors of Life magazine, a publication synonymous with iconic photography, honored his image by naming it one of “the 100 photographs that changed the world.” This designation underscores its status as a pivotal moment in the history of technology and human perception. Walden Kirsch, whose infant face unknowingly launched the era of computerized photography, later pursued a successful career in communications, working for companies like Intel, a direct descendant of the information technology revolution his father helped to start.

The process of converting an existing analog photograph into a digital format, as Kirsch did, was a proto-version of what Tophinhanhdep.com’s “Image Tools” now offer in advanced forms. Modern converters transform images between various digital formats, while optimizers and compressors refine digital files for efficient storage and transmission. Kirsch’s pioneering work, albeit rudimentary, initiated the crucial bridge between the physical and digital visual worlds, making possible the vast and diverse collections of digital wallpapers, backgrounds, and aesthetic photography that users explore and cherish today.

From Analog Scans to Self-Contained Digital Capture

The creation of the first digital image by scanning an analog photograph was a monumental step, but it still required an intermediary physical image. The next major leap in the evolution of digital imaging involved designing systems that could capture light directly in a digital format, removing the need for film or paper entirely. This move towards native digital capture was crucial for the seamless and instant imaging we experience today.

Pioneering Sensors: Peter Noble’s Active Pixel Sensor (1968)

The quest to create truly digital images, without an initial analog step, led to the development of sophisticated sensors capable of converting light directly into digital information. A pivotal breakthrough in this area came in 1968 with Peter Noble, who built one of the earliest sensors capable of performing this direct conversion. His invention was a type of photodetector known as an Active Pixel Sensor (APS).

Noble’s APS was revolutionary because it directly registered how light fell across its surface and translated this light intensity into digital data. Unlike Kirsch’s method, which involved scanning an already developed photograph, Noble’s sensor could create a digital image directly “from life.” This meant that an image could be formed in a purely digital format at the point of capture, eliminating the need for any analog intermediary. This innovation was a critical step toward the fully electronic cameras that would soon follow.

The Active Pixel Sensor, in its various iterations and advancements, became a fundamental component in virtually all modern digital cameras, including those in smartphones and advanced DSLRs. It underpins the ability to capture high-resolution photography instantly, a core offering on Tophinhanhdep.com. Without Noble’s early work on direct light-to-digital conversion, the dream of “digital photography” as a self-contained process would have remained elusive for much longer. His contribution paved the way for the development of compact, efficient digital imaging devices that would eventually democratize photography and visual content creation.

The Birth of the Digital Camera: Steven Sasson’s Kodak Prototype (1975)

Building upon the advancements in direct digital sensing, the concept of a self-contained digital camera emerged in the mid-1970s. The honor of inventing the first fully functional digital camera goes to Steven J. Sasson, an electronics engineer at Eastman Kodak in Rochester, New York. In 1975, Sasson was tasked by Kodak to explore the potential of digitizing images using a charged-coupled device (CCD).

CCDs, invented in 1969 by Willard Boyle and George E. Smith at Bell Labs, were sensors that could convert a two-dimensional light pattern into an electrical signal, which then formed an image. Sasson specifically utilized Fairchild Semiconductor’s 100x100-pixel CCD for his project. While CCDs could capture an image, they lacked the ability to store it permanently. This posed a significant challenge for Sasson: how to create an “all-electronic camera that didn’t use any consumables in the capturing and display of still photographic images.”

Sasson’s solution was to integrate the CCD into a camera body, pairing it with random-access memory (RAM) to temporarily hold the image data. From the RAM, the data was then transferred to a digital cassette tape – the most practical form of “digital storage” available at the time. Each cassette tape could store up to 30 images, a revolutionary concept for an era accustomed to film rolls with finite exposures.

The physical manifestation of Sasson’s prototype was a testament to inventive scavenging and engineering. He repurposed a lens and an exposure mechanism from a Kodak XL55 movie camera for the optics. These components were housed in a blue, rectangular box, which also featured a simple on/off switch that doubled as the shutter-release button. Beneath this visual component lay a complex array of half a dozen circuit boards and a power source of 16 AA batteries, all enclosed within an open steel frame. This frame was designed to unfold, allowing easier modification of the camera’s internal components. A portable Memodyne cassette recorder, attached to the side of the frame, held the storage tape. The entire contraption weighed a hefty 3.6 kilograms (about 8 pounds) and was roughly the size of a toaster.

Operating the camera was a sequential process: one flip of the switch turned it on, and a second flip initiated photo capture. The CCD captured the image in a mere 50 milliseconds. This raw analog signal was then fed through a Motorola analog-to-digital converter before being temporarily stored in a DRAM array of a dozen 4,096-bit chips. Finally, the digitized image was transferred to the cassette tape, a process that took a lengthy 23 seconds.

To complete his vision of a fully electronic photographic system, Sasson and his team also developed a playback unit. This device read the information from the cassette tape, converted the digital data into a standard NTSC signal, and then displayed the images on a conventional television screen. In December 1975, after a year of dedicated work, Sasson captured his first photo: an image of Kodak lab technician Joy Marshall. The initial display of this 100x100-pixel black-and-white image on a lab computer revealed its flaws; while distinct dark and light shades were rendered, intermediate tones appeared as static, making Marshall’s face almost indistinct. Sasson diligently addressed these issues, and he was granted a U.S. patent for the camera in 1978.

Despite the groundbreaking nature of Sasson’s invention, Kodak executives initially failed to foresee a significant market for it. The camera was never put into production, and Sasson was even restricted from discussing or demonstrating his prototype outside the company. However, Sasson remained undeterred, continuing his work on digital imaging. He later contributed to the development of one of the first commercially available digital cameras, the AP NC2000, in collaboration with Nikon in 1994. Today, Sasson’s original digital camera is proudly displayed at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C., recognized as an IEEE Milestone for its profound impact.

The skepticism from Kodak in the 1970s highlights the immense shift in perspective required to embrace digital photography fully. What seemed niche then is now universal. Sasson’s creation directly led to the “Digital Photography” category on Tophinhanhdep.com, forming the bedrock for high-resolution images, diverse editing styles, and the vast library of stock photos available to creators and enthusiasts alike. The challenges he faced with image quality and storage directly influenced the development of advanced “Image Tools” like compressors, optimizers, and AI upscalers, which ensure that today’s digital images are not only high-quality but also manageable and accessible.

The Digital Image Goes Global: The Internet Revolution

The journey of the digital image, from a theoretical concept to a scanned file and then to a directly captured photograph, culminated in its global dissemination through the World Wide Web. This final step transformed digital images from mere technological curiosities into a universal language of communication and expression.

The First Image on the World Wide Web (1992)

Shelford Bidwell’s original idea of “telephotography” was fundamentally about sharing images quickly with others across distances. This core aspiration found its ultimate realization with the advent of the World Wide Web, and a seemingly casual moment in July 1992 at CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, etched itself into history as the moment the first photograph was uploaded to this burgeoning global network.

The protagonists of this story were a band known as “Les Horribles Cernettes,” comprised of CERN staff members Angela Higney, Michele de Gennaro, Colette Marx-Neilsen, and Lynn Veronneau. They playfully described themselves as the “world’s greatest high-energy rock band,” despite their repertoire often leaning towards comedic 1950s doo-wop. Just before one of their performances, the band posed for a quick photograph, an ordinary analog photo taken on film, as was typical in 1992. The photographer was Silvano de Gennaro, a computer physicist at CERN and the band’s self-appointed manager.

De Gennaro, however, was also an early adopter and experimenter in computer image processing. He scanned the analog photograph of Les Horribles Cernettes and saved it as a .gif file on his color Macintosh computer. Utilizing one of the earliest versions of Photoshop (version one), he meticulously cut the band members from their original background and placed them against a simple baby blue backdrop, creating a low-quality promotional picture.

The serendipitous moment occurred when Tim Berners-Lee, the visionary creator of the World Wide Web, visited de Gennaro’s office. Berners-Lee saw de Gennaro’s digital photograph and, with a laugh, suggested that he create a “website” for the band on the still little-known computer network. Berners-Lee was actively experimenting with the Web’s potential beyond scientific data sharing, exploring its social communication functions across the CERN site.

Following this suggestion, Berners-Lee crafted a webpage to advertise events at CERN and uploaded de Gennaro’s image of Les Horribles Cernettes. The image itself was tiny—only about 120 pixels by 50 pixels, roughly the size of a postage stamp. This diminutive size was a practical necessity, as the early web infrastructure would have struggled considerably with larger image files. While the web already hosted some graphs and diagrams, this small picture held the distinct honor of being the very first photograph ever uploaded to the World Wide Web.

There were no grand celebrations or official acknowledgments at the time; it was simply another step in Berners-Lee’s ongoing experimentation. However, this seemingly minor act proved to be profoundly significant. As CERN staff began to communicate more through the Web, their conversations naturally drifted beyond work-related topics, transforming the platform into a space for social interaction. The Cernettes’ picture stood at the forefront of this tiny, yet ultimately world-changing, revolution. It symbolized the Web’s potential not just for information exchange, but for personal connection, entertainment, and cultural dissemination.

This milestone profoundly influenced how we interact with images today. The ability to “snap and send photos via the internet on our smartphones many times a day” is a direct descendent of that first upload. For Tophinhanhdep.com, this moment solidified the purpose of its vast collections. The first image on the web demonstrated the power of digital visuals to connect people, share experiences, and inspire. This principle is fundamental to Tophinhanhdep.com’s categories such as “Aesthetic,” “Trending Styles,” and “Mood Boards,” where the ease of sharing and discovery fosters creative communities and provides visual inspiration across the globe. It proved that digital images could indeed “go global,” becoming a universal language of the internet.

The Enduring Legacy: How Early Innovations Shape Modern Imaging

The journey from Shelford Bidwell’s theoretical “telephotography” in the 1880s to Russell Kirsch’s scanned baby photo in 1957, Steven Sasson’s digital camera in 1975, and finally, the first photograph on the World Wide Web in 1992, represents a remarkable saga of innovation. These seemingly disparate milestones collectively forged the path for the dynamic, image-rich digital world we experience daily.

The Pillars of Digital Photography and Visual Design

Traditionally, photography was a natural chemical reaction, discovered rather than invented, relying on the actions of light on various chemicals to leave visible markings on film, paper, glass, or metal. A digital photograph, however, is an entirely different beast. It is not a physical imprint but a construct of binary information—a complex set of instructions that tells computers how to deconstruct, store, and reassemble a visual scene. For a digital image to exist, brilliant minds like Bidwell, Kirsch, Noble, and Sasson had to perform a monumental intellectual leap: to conceive of converting light and pictures into electronic pulses, into data, that could be transmitted, stored, manipulated, and faithfully rebuilt.

This fundamental shift from analog chemistry to digital data forms the bedrock of modern visual culture. Without these early pioneers, the fields of graphic design, digital art, and sophisticated photo manipulation simply would not exist in their current forms. The ability to create, edit, and render visual content with unparalleled flexibility and precision is a direct consequence of the digital image being a collection of editable, transmittable data points rather than an unchangeable chemical reaction on a surface.

This legacy is palpable in every corner of Tophinhanhdep.com. Our “Visual Design” section, encompassing graphic design, digital art, and photo manipulation, directly leverages the principles established over a century ago. The nuanced “Editing Styles” in photography are possible because digital images offer layers of control and flexibility that analog images never could. The aesthetic qualities of images, whether vibrant “Nature” scenes or profound “Sad/Emotional” expressions, are now expertly captured and enhanced through digital means, transforming raw light into stunning visual narratives. The vast collections of “Wallpapers” and “Backgrounds” that enrich our digital lives are a testament to the endless possibilities that arose from these early digital breakthroughs.

Empowering Creation with Tophinhanhdep.com’s Tools and Collections

The historical evolution of the digital image is not merely a fascinating historical anecdote; it is the very foundation upon which platforms like Tophinhanhdep.com are built. The innovations from Bidwell’s telephotography to Sasson’s camera and Berners-Lee’s web upload directly inform and empower the diverse services and resources offered today.

Images (Wallpapers, Backgrounds, Aesthetic, Nature, Abstract, Sad/Emotional, Beautiful Photography): The sheer variety and quality of images available on Tophinhanhdep.com are a direct result of the continuous advancement in digital imaging. Russell Kirsch’s grainy 176-pixel image was the first step towards the high-resolution, pixel-dense wallpapers and backgrounds users now expect. The digital format allows for endless permutations and styles, enabling the creation of entire collections dedicated to “Aesthetic,” “Nature,” “Abstract,” and “Sad/Emotional” themes, each meticulously curated to provide the perfect visual experience. Beautiful photography, once confined to print, can now be displayed globally in pristine digital clarity, becoming instantly accessible to millions seeking inspiration or decoration.

Photography (High Resolution, Stock Photos, Digital Photography, Editing Styles): The journey from Steve Sasson’s 0.8-megapixel prototype to today’s multi-megapixel cameras underscores the relentless pursuit of “High Resolution” in “Digital Photography.” Tophinhanhdep.com serves as a vital hub for this evolution, offering vast libraries of “Stock Photos” that meet the demands of modern visual content. The inherent digital nature of these images means they are perfectly suited for “Editing Styles,” allowing photographers and designers to refine, enhance, and transform visuals far beyond what was possible in the darkroom. The digital image’s flexibility is paramount, enabling precise adjustments for light, color, and composition.

Image Tools (Converters, Compressors, Optimizers, AI Upscalers, Image-to-Text): The technical challenges faced by early pioneers—from converting analog light into digital signals to managing bulky file sizes—directly led to the development of sophisticated “Image Tools.” Kirsch’s initial scanning process was a basic form of conversion; today, Tophinhanhdep.com provides advanced “Converters” to seamlessly change image formats. Sasson’s struggle with storing 30 images on a cassette tape highlighted the need for efficiency, giving rise to “Compressors” and “Optimizers” that reduce file size without compromising quality. Furthermore, the imperfections of early digital images, such as Joy Marshall’s indistinct face in Sasson’s first photo, have been overcome by incredible advancements like “AI Upscalers,” which can dramatically improve resolution and detail. The capacity to treat images as data also facilitates “Image-to-Text” functionalities, bridging the visual and textual worlds.

Visual Design (Graphic Design, Digital Art, Photo Manipulation, Creative Ideas): The very existence of digital images opened the floodgates for “Graphic Design” and “Digital Art.” The ability to manipulate pixels, layer images, and create entirely new visual compositions digitally was a direct outcome of this technological shift. Programs like Photoshop, used in its nascent form to create the first web photo, revolutionized “Photo Manipulation.” Tophinhanhdep.com is a platform where these “Creative Ideas” are nurtured and realized, providing the resources and inspiration for designers and artists to push the boundaries of visual expression.

Image Inspiration & Collections (Photo Ideas, Mood Boards, Thematic Collections, Trending Styles): The unparalleled accessibility and shareability of digital images, demonstrated by the first photo on the World Wide Web, have fostered a culture of visual inspiration. Tophinhanhdep.com curates “Photo Ideas” and allows users to create “Mood Boards” from vast “Thematic Collections,” making it effortless to discover and engage with “Trending Styles.” This collective visual dialogue, where images are shared, repurposed, and celebrated, is a direct heir to the early digital pioneers who envisioned a world where pictures could be more than just physical artifacts—they could be universally accessible, infinitely adaptable, and powerfully communicative digital entities.

In conclusion, the journey of the digital image is a compelling narrative of scientific curiosity, persistent engineering, and visionary foresight. From Shelford Bidwell’s conceptual breakthroughs to Russell Kirsch’s groundbreaking scan, Steven Sasson’s pioneering digital camera, and the indelible moment a band’s photo graced the World Wide Web, each step built upon the last, transforming how we perceive and interact with the visual world. Today, Tophinhanhdep.com stands on the shoulders of these giants, offering a vibrant testament to the enduring power and limitless potential of the digital image, continuing to innovate and inspire in the ever-evolving landscape of pixels and possibility.