When Was the First Instantaneous Transmission of Images Demonstrated?

The quest to transmit images across distances, much like the mythical feats of instantaneous teleportation, has captivated humanity for centuries. While the concept of true “instantaneous transmission” might evoke fantastical abilities like those seen in Dragon Ball’s “Instant Transmission” (Shunkan Idō), the technological journey to achieve real-time visual communication has been a long and groundbreaking one. This article delves into the historical milestones of image transmission, tracing its evolution from crude mechanical systems to the sophisticated digital imagery we experience today, and highlighting how platforms like Tophinhanhdep.com embody the modern realization of this enduring ambition.

The Dawn of Image Transmission: Mechanical Pioneers

The idea of sending images through wires or air has roots stretching back to the 19th century, long before the digital age made high-resolution images and visual design accessible to everyone. Early pioneers envisioned a world where visual information could travel as swiftly as sound.

Early Concepts and Breakthroughs

The groundwork for instantaneous image transmission was laid with the development of facsimile technology. Alexander Bain’s facsimile machine in the 1840s and Giovanni Caselli’s pantelegraph in the 1850s proved that still images could be transmitted over telegraph lines. These early innovations, while not “live” television, established the fundamental principle of converting visual information into electrical signals for remote reconstruction. The discovery of selenium’s photoconductivity by Willoughby Smith in 1873 was a pivotal moment, as selenium cells became essential components in early mechanical scanning systems, acting as the “eyes” that converted light into electrical current.

A significant conceptual leap came in 1884 when German student Paul Julius Gottlieb Nipkow patented the Nipkow disk. This spinning disk with a spiral pattern of holes was designed to sequentially scan an image point by point, breaking it down into a series of electrical impulses. Though Nipkow himself never built a working model, his invention became the cornerstone of most mechanical television systems for decades. These early, low-resolution images, perhaps resembling abstract art or simple graphic design, were the rudimentary ancestors of today’s rich visual content available on Tophinhanhdep.com.

The word “television” itself was coined by Constantin Perskyi in 1900, at the International Electricity Congress in Paris, reflecting the growing ambition to achieve “seeing at a distance.” However, it was German physicist Ernst Ruhmer who achieved what could be considered the first demonstration of the instantaneous transmission of images in 1909. Ruhmer arranged 25 selenium cells as picture elements for a receiver and announced the transmission of simple, geometric shapes over a telephone wire from Brussels to Liège, Belgium, a distance of 70 miles (115 km). This rudimentary system, while limited to 5x5 pixels, was hailed as “the world’s first working model of television apparatus,” proving the concept of real-time visual data transfer. The cost was prohibitive, estimating a 4,000-cell system at £60,000, illustrating the vast chasm between rudimentary proof-of-concept and widespread accessibility that modern platforms like Tophinhanhdep.com effortlessly bridge with high-resolution, readily available images.

Following Ruhmer, French scientists Georges Rignoux and A. Fournier independently demonstrated a system using a matrix of 64 selenium cells (8x8 pixels) to transmit individual letters of the alphabet “several times” each second. In 1911, Boris Rosing and Vladimir Zworykin (who would later become a key figure in electronic television) developed a system that used a mechanical mirror-drum scanner to transmit “very crude images” over wires to a Braun tube (cathode-ray tube or CRT) receiver. While these images were still incredibly basic and not yet truly “moving,” they marked crucial steps toward combining mechanical scanning with electronic display.

John Logie Baird and the Public Eye

The invention of the amplifying vacuum tube (triode) by Lee de Forest in 1907 provided the necessary amplification for practical television designs. This paved the way for Scottish inventor John Logie Baird, who in 1925 built some of the first prototype video systems utilizing the Nipkow disk.

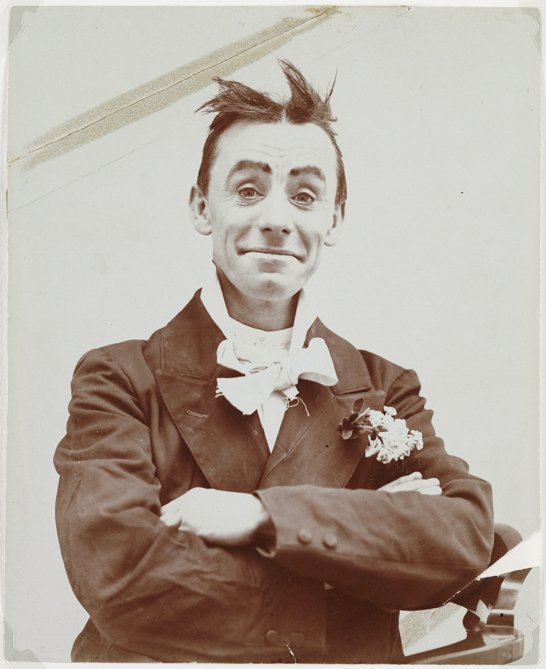

On March 25, 1925, Baird gave the first public demonstration of televised silhouette images in motion at Selfridge’s Department Store in London. His scanner, initially operating at a mere five images per second, was below the threshold for smooth apparent motion (typically 12 images/second). Recognizing this limitation, Baird quickly refined his system. By January 26, 1926, he achieved a scan rate of 12.5 images per second and publicly demonstrated the transmission of images of a face in motion by radio at his laboratory in London to members of the Royal Institution and a newspaper reporter. This event is widely recognized as the world’s first public television demonstration of live, moving images.

Baird’s system used a Nipkow disk for both scanning and display. A brightly illuminated subject was placed before a spinning disk, and the light reflected was captured by a thallium sulfide photocell, converted into an electrical signal, and transmitted via AM radio waves. At the receiver, a synchronized Nipkow disk and a neon lamp recreated the image, varying the lamp’s brightness in proportion to the original scene. His disk produced a 30-scan line image, just enough to discern a human face – a stark contrast to the high resolution photography and beautiful photography found on Tophinhanhdep.com today.

Baird continued to push boundaries, transmitting a signal over 438 miles of telephone line between London and Glasgow in 1927. In 1928, his company broadcast the first transatlantic television signal between London and New York, and the first shore-to-ship transmission. By 1931, he made the first outdoor remote broadcast of The Derby. His mechanical system reached a peak of 240 lines of resolution on BBC television broadcasts by 1936, demonstrating remarkable clarity for its time, though still a far cry from modern digital imagery.

Other significant figures in this mechanical era included American inventor Charles Francis Jenkins, who transmitted moving silhouette images for witnesses in December 1923 and publicly demonstrated synchronized transmission of silhouette pictures in June 1925 using a 48-line lensed disk scanner. In Japan, Kenjiro Takayanagi demonstrated a 40-line system with a Nipkow disk scanner and CRT display in 1926, improving it to 100 lines by 1927 and transmitting human faces in half-tones by 1928.

Perhaps one of the most dramatic demonstrations of mechanical television came from Herbert E. Ives and Frank Gray of Bell Telephone Laboratories on April 7, 1927. Their system featured both small (2x2.5 inches) and large (24x30 inches) viewing screens capable of reproducing “reasonably accurate, monochromatic moving images” with synchronized sound over copper wire and radio links. Television historian Albert Abramson noted, “It was in fact the best demonstration of a mechanical television system ever made to this time.” These pioneering efforts, while technologically primitive by today’s standards, laid the essential foundation for all subsequent visual media, including the high-quality wallpapers and backgrounds we now take for granted.

The Evolution to Electronic and Digital Images

The mechanical era, with its spinning disks and limited resolution, eventually gave way to more advanced electronic systems, marking a significant leap toward the “instantaneous” and high-fidelity image transmission we experience today.

The Ascendance of Electronic Television

Mechanical television systems, despite their ingenious designs, inherent limitations. They generally produced small, dim images with low resolution, typically ranging from 30 to about 120 lines, which hindered their popular appeal. Disks beyond a certain diameter became impractical, limiting the achievable resolution. The demand for higher quality and larger displays spurred the development of all-electronic television.

The transition began in earnest with Philo Farnsworth, who in September 1927, demonstrated the first fully electronic television system with his “Image Dissector” camera tube in San Francisco. Farnsworth’s system, devoid of mechanical moving parts, transmitted its first image – a simple straight line. He refined his system, holding a public demonstration for the press in September 1928, and by 1929, transmitted the first live human images, including a 3.5-inch image of his wife. Similarly, Vladimir Zworykin, who had worked with Rosing, developed the “Iconoscope” camera tube in the early 1930s, further advancing electronic image capture.

The first public demonstration of an all-electronic television system using a live camera was given by Philo Farnsworth at the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia on August 25, 1934. This marked a pivotal moment, signaling the practical viability of electronic television. By the mid-1930s, electronic-scan technology rapidly superseded mechanical systems. Companies like Philco and DuMont Laboratories, alongside Farnsworth’s own endeavors, achieved resolutions of 400 to over 600 lines. After years of litigation, RCA paid Farnsworth $1 million for his patents in 1939, and subsequently began demonstrating all-electronic television at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York City. The last mechanical television broadcasts in the U.S. ceased in 1939, giving way to the electronic era.

The shift to electronic television was akin to the modern evolution of digital photography and image editing styles. It brought about a dramatic improvement in image quality, stability, and the potential for larger displays, laying the groundwork for the rich visual experiences we now enjoy on Tophinhanhdep.com.

Color and High-Definition Milestones

The pursuit of realism in image transmission naturally led to the development of color television. John Logie Baird had experimented with color television as early as 1928, foreshadowing future innovations. In 1940, Peter Goldmark of CBS developed a more advanced field-sequential color system, where a mechanical disc at the camera filtered colors, and a synchronized disc at the receiver painted them onto the CRT. This system was notable for its use in early color broadcasts and even in the Apollo Moon missions, where lunar color cameras employed color wheels to send field-sequential color images back to Earth.

However, the ultimate success lay with all-electronic, simultaneous color systems. RCA demonstrated the first such system to the FCC on January 29, 1947, which would eventually become the NTSC standard. While CBS’s field-sequential system initially won head-to-head testing and launched color broadcasts in 1951, the burgeoning market of black-and-white television sets created resistance to a non-compatible system. The NTSC-compatible electronic color system gained traction, leading to widespread adoption through the 1950s and 1960s. By the 1966–67 broadcast season, all major networks were airing full-color prime time schedules, and by 1972, color television set sales surpassed black-and-white sales in the U.S. This transformation in visual design brought a new dimension to storytelling and entertainment, fundamentally altering how we perceive and appreciate images.

The relentless drive for “instantaneous transmission of images” also pushed the boundaries of display technology beyond CRTs. In 1988, Sharp Corporation introduced the first commercial LCD (Liquid Crystal Display) television. Plasma displays also emerged, offering competitive performance. The latest significant advancement came with LED (Light Emitting Diode) backlighting for LCD TVs, exemplified by the Sony Qualia 005 in 2004. These developments continually improve the clarity, contrast, and vibrancy of images, enabling the display of stunning high-resolution photography and aesthetic visuals that are central to platforms like Tophinhanhdep.com.

The Fictional Ideal vs. Technological Reality: “Instant Transmission”

The historical journey of image transmission, while remarkable, underscores the fundamental differences between scientific advancement and pure fantasy. The original search term, “when was the first instantaneous transmission of images demonstrated,” ironically leads to information about Dragon Ball’s “Instant Transmission” (Shunkan Idō), a technique that perfectly encapsulates the idealized, magical version of instant movement and perception.

In the Dragon Ball universe, “Instant Transmission” allows users, most notably Goku, to instantly teleport across vast distances—from meters to light-years, and even between dimensions like the living world and the Other World. The technique typically involves placing index and middle fingers on the forehead for concentration, locking onto a particular individual’s “ki signature,” and then instantly appearing at their location. This power is truly instantaneous; there is no travel time, no waiting for signals to propagate. It is the ultimate expression of the desire for immediate presence.

This fictional ability serves as a powerful contrast to the painstaking, incremental steps taken by scientists and inventors to achieve real-world instantaneous image transmission. While Ruhmer, Baird, and Farnsworth pushed the boundaries of what was technologically possible, their “instantaneous” transmissions were still bound by the laws of physics—the speed of light, signal processing delays, and the mechanical or electronic scanning times. The “instant” in their demonstrations referred to the real-time nature of the transmission, not a magical transcendence of space and time.

The appeal of “Instant Transmission” in Dragon Ball speaks to a deep human desire for absolute immediacy, a wish to overcome physical barriers effortlessly. In a way, the evolution of image transmission technology—from telegraphic facsimiles to global high-definition streaming—is our continuous, albeit earthbound, attempt to mimic this ideal. Every improvement in bandwidth, processing speed, and display technology brings us closer to a perceived instantaneity, where images and visual content from anywhere in the world can appear on our screens in fractions of a second. This pursuit of the “instant” is what drives the platforms like Tophinhanhdep.com, aiming to deliver image inspiration and thematic collections to users with unparalleled speed and convenience.

Modern Image Transmission and Tophinhanhdep.com’s Vision

Today, the concept of “instantaneous transmission of images” has been largely realized through the pervasive reach of the internet and digital technology. What once required complex mechanical contraptions or dedicated broadcasting infrastructure now happens seamlessly through our smartphones, computers, and myriad connected devices.

The modern digital ecosystem, much like the advancements in early television, continually strives for higher quality and greater immediacy. The images on our screens, whether wallpapers, backgrounds, aesthetic nature shots, or abstract digital art, are the result of sophisticated capture, processing, and transmission technologies. High-resolution photography and stock photos are now standard, and the fidelity of transmitted images is astounding compared to the 30-line pictures of Baird’s era.

Platforms like Tophinhanhdep.com stand at the forefront of this digital visual revolution. They embody the culmination of over a century of innovation in image transmission, offering:

- Images (Wallpapers, Backgrounds, Aesthetic, Nature, Abstract, Sad/Emotional, Beautiful Photography): The ability to access a vast array of visually stunning images, tailored to diverse tastes and moods, is a direct outcome of the journey toward instantaneous visual communication. Users can instantly browse, download, and share high-quality visuals for personal or professional use, transforming their digital environments or creative projects.

- Photography (High Resolution, Stock Photos, Digital Photography, Editing Styles): The demand for crisp, detailed images has driven advancements in digital photography. Tophinhanhdep.com curates collections of high-resolution stock photos and showcases various digital photography and editing styles, reflecting the modern aesthetic sensibilities that evolved from the basic image-making of yesteryear. The transmission of these complex, data-rich files in mere moments is a testament to the “instantaneity” we’ve achieved.

- Image Tools (Converters, Compressors, Optimizers, AI Upscalers, Image-to-Text): The “tools” of modern image transmission are no longer spinning disks but sophisticated software. Converters adapt formats, compressors reduce file sizes for faster transmission without significant loss of quality (the modern equivalent of optimizing signal bandwidth), and optimizers fine-tune images for web delivery. AI upscalers, a marvel of contemporary technology, can even enhance lower-resolution images, much like early engineers continuously sought to improve scan lines. Image-to-text tools demonstrate the integration of visual data with other forms of information, enabling powerful new applications. These tools on Tophinhanhdep.com enhance the efficiency and versatility of image handling, making the experience truly “instant.”

- Visual Design (Graphic Design, Digital Art, Photo Manipulation, Creative Ideas): The instantaneous transmission of images has profoundly impacted the fields of visual design and digital art. Designers and artists can collaborate in real-time, share proofs instantly, and draw inspiration from a global pool of visual content. Photo manipulation, once a laborious darkroom process, is now a dynamic digital art form facilitated by instant feedback and sharing capabilities. Tophinhanhdep.com serves as a hub for graphic design elements, digital art examples, and creative ideas, fostering a vibrant ecosystem of visual creation and consumption.

- Image Inspiration & Collections (Photo Ideas, Mood Boards, Thematic Collections, Trending Styles): The sheer volume and accessibility of images available for instant transmission have revolutionized how we find inspiration. Mood boards can be assembled in minutes, thematic collections curated with a few clicks, and trending styles identified and adopted almost immediately. Tophinhanhdep.com provides rich thematic collections and insights into trending styles, demonstrating how the ability to transmit images instantaneously has transformed the creative process from a solitary, limited pursuit to a collaborative, boundless exploration.

From Ernst Ruhmer’s 25-pixel shapes transmitted over telegraph wires in 1909 to John Logie Baird’s fuzzy silhouettes broadcast to a handful of people in 1925, and through the evolution to electronic television, color broadcasts, and eventually the global digital image networks of today, the journey towards instantaneous image transmission has been relentless. While we may not possess the magical “Instant Transmission” of fictional heroes, humanity’s ingenuity has engineered a reality where images, from beautiful photography to abstract art, can traverse the globe in mere milliseconds, shaping our world and fueling our creative endeavors. Platforms like Tophinhanhdep.com are not just repositories of images; they are a testament to this incredible historical pursuit, offering a truly instantaneous window into the world of visual content and empowering users with the tools and inspiration to create their own.