Poetic Imagery: Crafting Unforgettable Visuals with Words – Which Poems Master Concrete Images?

Close your eyes for a moment. What images spring to mind? Perhaps the vibrant burst of citrus on your tongue, the distinct grit of sand beneath your feet, or the soft, hypnotic dance of candlelight on a textured wall. These are the powerful “concrete images” that poetry, much like photography and visual art, thrives upon. They are the sensory brushstrokes that transport us, making a written world feel tangible, tasted, heard, smelled, and seen. At Tophinhanhdep.com, we understand the profound impact of compelling visuals, whether they’re captured through a lens, rendered digitally, or conjured purely through the masterful arrangement of words.

While the art of visual storytelling often falls to photographers, graphic designers, and digital artists, poets have long been the original architects of inner landscapes, using language to build vivid realities within the reader’s mind. But not all poems are created equal in their ability to paint these sensory masterpieces. So, which poems truly excel at packing their verses with the most stunning, substantial images, spilling them onto the page like a treasure trove of visual and sensory delights? Let’s dive into the fascinating world where poetic language meets the power of the tangible, exploring how these literary feats can inspire everything from high-resolution photography to cutting-edge digital art on Tophinhanhdep.com.

The Art of Sensory Immersion: Unveiling Concrete Images in Poetry

Poetry’s unique magic lies in its capacity to evoke entire worlds with a carefully chosen phrase. When we talk about “concrete images” in poetry, we are referring to details that directly appeal to our five senses. Unlike abstract concepts or emotions, concrete imagery presents specific, palpable information that allows the reader to not just understand, but experience the poem. This direct sensory engagement is the very essence of powerful visual communication, a principle that resonates deeply with the mission of Tophinhanhdep.com to provide and inspire with compelling images.

What Makes an Image Concrete?

To grasp the power of concrete imagery, consider the distinction between saying “I am sad” and “my tears taste like salt and rust, pooling in the grooves of yesterday’s crossword.” The first statement informs; the second plunges you into the raw, aching reality of the emotion through taste and sight. Concrete imagery is poetry’s equivalent of a vivid photograph or a meticulously designed visual. It leverages details that trigger your senses:

- Sights: Colors, shapes, sizes, movements, light, shadows.

- Sounds: Whispers, roars, rustles, melodies, silence.

- Textures: Smooth, rough, gritty, soft, sharp, wet.

- Smells: Sweet, pungent, earthy, metallic, floral.

- Tastes: Bitter, sweet, salty, sour, umami.

This sensory richness is what transforms a poem from a mere collection of words into a full-blown cinematic experience playing inside your head. It’s the reason a well-crafted line can be as evocative as any wallpaper on Tophinhanhdep.com, providing a background for your thoughts, a mood, or a striking aesthetic.

Now, for a standout example often lauded as a champion of sensory overload, William Carlos Williams’ The Red Wheelbarrow takes the crown. Yes, the poem is remarkably brief – just sixteen words – yet its impact is monumental. Let’s dissect its sensory precision:

- so much depends

- upon

- a red wheel

- barrow

- glazed with rain

- water

- beside the white

- chickens.

Every line here is a brushstroke, a perfectly placed pixel in a high-resolution image. The “red wheelbarrow” isn’t merely red; it’s rain-soaked, glistening, almost pulsating with life against the damp earth. The “white chickens” are not just white; they provide a stark, almost photographic contrast to the vibrant barrow and the surrounding environment. You can vividly see the rainwater pooling, almost hear the faint cluck of the chickens, and smell the damp, earthy air. Williams doesn’t explain why “so much depends” on this humble scene. Instead, he hands you a literary Polaroid, allowing you to feel the inexplicable weight of its mystery. It’s a small poem with the gravitational pull of a profound aesthetic background.

But Williams is by no means the only master. Consider Sylvia Plath’s Black Rook in Rainy Weather. She transforms a dreary, soaked afternoon into a symphony of textures and subtle visual cues: the rook’s feathers “evasion” like damp playing cards, the “mute sky” pressing down with the weight of a heavy lid, the “minor light” desperately struggling through dense clouds. Plath doesn’t just describe gloom; she makes you wade through it, evoking the feeling of galoshes sinking into mud, a powerful example of emotional aesthetic imagery suitable for a sad/emotional collection on Tophinhanhdep.com.

Or delve into Seamus Heaney’s Blackberry-Picking, where the fruit isn’t just sweet; it’s “a glossy purple clot” that stains your hands “like thickened wine.” The poem overflows with the scent of summer’s ripeness and eventual rot, the thrill of harvest intertwined with the pangs of decay. You can almost taste the berries, feel their sticky juice, and smell the late summer air – an excellent inspiration for nature photography focused on high-resolution details and textural richness.

The true genius of concrete imagery, however, isn’t simply about volume; it’s about The Precision of Concrete Imagery. Emily Dickinson’s A Bird came down the Walk condenses a lifetime of meticulous observation into a bird’s “velvet” head and “frightened beads” of eyes. Robert Frost’s Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening transforms a quiet night into a delicate tapestry of “easy wind and downy flake.” Each image is a self-contained snow globe – tiny, perfect, and shaking you into a new, fully realized world. This precision teaches us the value of minute details, a crucial lesson for any photographer striving for high-resolution clarity or a graphic designer aiming for impactful simplicity.

A Look at Concrete Poetry: Where Words Become Visual Art

While the term “concrete images” primarily refers to sensory details within poetic language, there exists another fascinating realm where poetry becomes literally concrete: Concrete Poetry. This poetic form takes visual communication to its extreme, using the physical arrangement of words, letters, and typography on the page to create an image or shape that directly relates to the poem’s theme. On Tophinhanhdep.com, where visual design and digital art reign supreme, concrete poetry offers a rich historical precedent for the convergence of text and imagery.

What Is a Concrete Poem?

A concrete poem, often referred to as visual or shape poetry, is a unique blend of linguistic and visual art. In this form, the visual arrangement of the text is as significant as the words themselves. Unlike traditional poetry, which relies mainly on the meaning and sound of words, concrete poetry emphasizes the physical form of the text to convey its message. The words, letters, and lines are meticulously arranged in shapes, patterns, or even abstract designs that reflect the poem’s subject, creating a visual representation that profoundly enhances the reader’s experience.

Imagine a love poem meticulously arranged in the shape of a heart, or a Christmas verse forming the outline of a Christmas tree. This is the essence of concrete poetry. It challenges the reader to engage with the poem not just through reading, but also through seeing. For visual designers and artists on Tophinhanhdep.com, this form offers powerful insights into how typography and layout can become integral parts of storytelling and emotional conveyance, serving as a direct inspiration for creative ideas and photo manipulation techniques.

Famous Examples of Concrete Poetry: Shaping Meaning Visually

The tradition of shaped poetry dates back to ancient Greek Alexandria, where poems were crafted into the forms of eggs, wings, and musical instruments. However, the term “concrete poetry” gained prominence in the mid-20th century among avant-garde poets. These works are foundational for understanding how text itself can be an image, directly influencing principles of visual design and digital art that we feature on Tophinhanhdep.com.

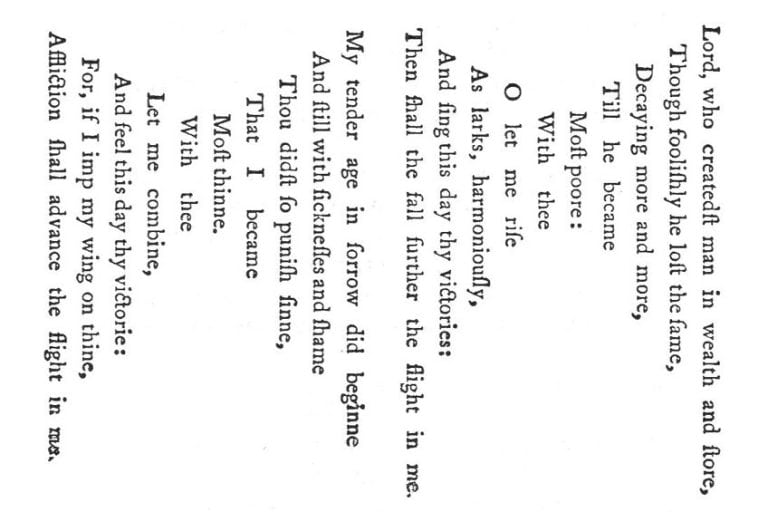

One of the earliest and most celebrated examples is Easter Wings (1633) by George Herbert. This 17th-century poem is structured to visually mimic a pair of open wings, tapering inwards and then expanding outwards across two stanzas. As Herbert was a priest, the wing shape symbolizes spiritual ascent, the soul’s flight from the fallen state to redemption. The visual form here isn’t a mere embellishment; it’s integral to the poem’s spiritual message, creating a profound connection between the visual and the thematic. This kind of symbolic visual storytelling offers fantastic inspiration for thematic collections or aesthetic photography that blends abstract and meaningful forms.

Another iconic example is The Mouse’s Tale (1865) by Lewis Carroll, famously appearing in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Carroll, a master of wordplay and whimsy, arranges the poem’s lines to visually form the winding, tapering shape of a mouse’s tail. This playful design is a clever pun on the word “tale,” as the mouse narrates its “long and sad tale.” Beyond its humor, the poem subtly satirizes the judicial system, with its convoluted form reflecting the twisting nature of legal arguments. For those seeking creative ideas or unique graphic design approaches on Tophinhanhdep.com, The Mouse’s Tale demonstrates how text can be both narrative and playful, a digital art piece in itself.

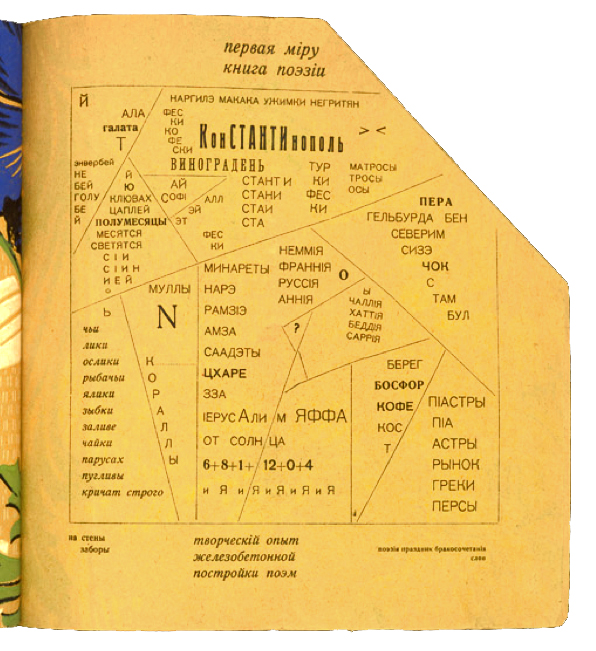

Moving into the 20th century, Zang Tumb Tumb (1912–1914) by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti stands as a revolutionary work of concrete poetry. Marinetti, a central figure in the Futurist movement, used an explosion of typography, fragmented words, and onomatopoeic sounds to depict the Siege of Adrianople, which he witnessed as a reporter. The poem employs varied fonts, sizes, and orientations, along with lines, circles, and squiggles, to simulate the chaos, sounds (like gunfire and explosions), and mechanized violence of war. Zang Tumb Tumb is a powerful example of how typography can transcend language to create an immersive visual and auditory experience, directly inspiring digital artists and graphic designers on Tophinhanhdep.com exploring abstract art, photo manipulation, and dynamic visual storytelling.

Historical Context and Evolution of Concrete Poetry

The journey of concrete poetry, from ancient shaped verses to avant-garde manifestos, mirrors the broader evolution of visual art and design. Its historical context reveals a continuous human fascination with expressing meaning not just through content, but through form – a principle deeply embedded in every image we curate on Tophinhanhdep.com.

While the conceptual roots of concrete poetry can be traced back to antiquity with Greek pattern poems, its modern incarnation truly began to take shape in the early 20th century. Figures like the French poet Guillaume Apollinaire led the charge with his Calligrammes (1918), where poems were literally drawn into the shapes of objects they described, like a necktie or a fountain. Apollinaire’s work established a vital precedent for poets who sought to break free from traditional linear verse and explore the visual potential of language.

The early 20th century was a hotbed of avant-garde movements – Futurism, Dada, and Surrealism – all of which experimented with typography and layout. Italian Futurists, including Marinetti, used dynamic layouts to reflect speed, technology, and violence, pushing the boundaries of what poetry could be. Vasily Kamensky, a Russian Futurist, even coined the term “ferro-concrete poems” in 1914 for his typographically bold works, foreshadowing the later official naming of the movement.

The specific term “concrete poetry” itself emerged in the 1950s, largely popularized by a group of Brazilian poets known as the Noigandres group (Augusto de Campos, Haroldo de Campos, and Décio Pignatari). Influenced by minimalist and abstract art, they sought to strip poetry down to its linguistic essence, focusing on the word as an object rather than a vehicle for discourse. They viewed the poem as a “constellation” of words, meant to be apprehended instantaneously like a visual image or a traffic sign. German poet Eugen Gomringer, a contemporary of the Brazilians, further articulated this philosophy in his manifesto, stating that a concrete poem should be “a reality in itself” rather than a statement about reality.

Since then, concrete poetry has diversified, embracing everything from minimalist arrangements of letters to complex visual puzzles. The advent of digital platforms has given it new dimensions, allowing for animated concrete poems and interactive text-based art. These shifts highlight the enduring appeal and adaptability of blending text with visual artistry, constantly inspiring new forms of digital art and creative ideas for our users on Tophinhanhdep.com.

Concrete Images in the Digital Age: Inspiration for Visual Creators

The world of poetry, particularly concrete imagery and concrete poetry, offers an inexhaustible wellspring of inspiration for the visual content creators active on Tophinhanhdep.com. The very act of a poet striving to render the intangible tangible through words provides a blueprint for photographers, graphic designers, and digital artists.

Poets, in their quest to evoke “the sharp flavor of citrus” or “the gritty crunch of sand,” are essentially crafting mental mood boards. These vivid descriptions can directly inform the thematic collections you might curate on Tophinhanhdep.com, guiding you to seek out specific textures, colors, or emotional tones in your photography. A poem describing a serene forest at dawn might inspire a collection of nature backgrounds, emphasizing soft light and misty air. Conversely, a poem filled with raw, emotional concrete images could be the perfect prompt for a series of sad/emotional wallpapers, capturing vulnerability and depth without explicit narratives.

From Text to Canvas: Translating Poetic Vision into Visual Art

For photographers, studying concrete imagery in poetry is akin to attending a masterclass in observation and composition. The poet’s precision in selecting a “red wheelbarrow, glazed with rainwater” teaches us to look for specific details, textures, and lighting conditions that elevate an ordinary scene to something extraordinary. This attention to detail is paramount in high-resolution photography and in creating stunning stock photos. How can an image convey the feeling of rainwater glazing a surface? What editing styles enhance the “vibrant tone” against the “stark contrast” of white chickens? Poetic descriptions provide these very questions, leading to more intentional and impactful visual outcomes.

Graphic designers and digital artists, on the other hand, can draw direct parallels from concrete poetry. The manipulation of typography, the intentional arrangement of letters to form shapes, and the use of negative space are fundamental principles in both art forms. The creative ideas showcased in poems like Easter Wings or The Mouse’s Tale are essentially early forms of visual branding or logo design, where form and meaning are inextricably linked. Imagine a logo for a literary magazine designed in the style of concrete poetry, using its title to form a recognizable shape. The abstract and expressive layouts of works like Marinetti’s Zang Tumb Tumb can inspire dynamic digital art pieces, using text elements as visual components within a larger composition, or even influencing photo manipulation techniques that integrate textual elements into images for aesthetic impact.

Leveraging Image Tools for Poetic Visuals

The connection between poetic imagery and the tools available on Tophinhanhdep.com extends beyond mere inspiration. Our platform’s image tools, designed to enhance, optimize, and transform visuals, can be seen as modern instruments for bringing poetic visions to life:

- AI Upscalers: When a poem describes a scene with incredible, almost microscopic detail, an AI upscaler could be used to enhance a corresponding photograph, pushing its resolution to match the vividness of the poetic description.

- Image-to-Text Converters: While primarily for reverse engineering, these tools highlight the inherent connection between visual data and textual representation. Understanding how AI interprets visuals can inform a photographer’s compositional choices, ensuring their images convey specific “concrete” meanings.

- Optimizers and Compressors: Just as a poet chooses each word carefully to maximize impact within a limited space, optimizers help ensure that the high-resolution, aesthetically rich images inspired by poetry are delivered efficiently, maintaining their visual integrity while being practical for web use.

Ultimately, whether you are crafting a wallpaper for your desktop, designing a new digital art piece, or seeking inspiration for your next photographic endeavor on Tophinhanhdep.com, remember the profound power of concrete images. They are the essence of lived experience, distilled into art. By engaging with poetry that excels in this sensory craft, you open new avenues for visual thinking, enabling you to create images that don’t just depict, but truly immerse and resonate with your audience. The world never looked so dazzling, especially when seen through the dual lens of poetic and visual art.